Abstract

How did armed forces behave in response to dissent, political instability and territorial disintegration during the collapse of the Soviet Union? To date, substantial attention has been cast on the 1991 August coup attempt, yet our understanding of other potential instances of defection remains incomplete. This study undertakes a comparative analysis of defection throughout 15 Soviet republics. Results reveal that 13 republics experienced subordinates defecting and three experienced commanders defecting. In total, four different pathways led to defection. These findings produce the first comparative observations of defection in this historical time period and lend support to the claim that this phenomenon is equifinal in nature.

Keywords

Introduction

Throughout the 74 years of its existence, the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) evolved into a superpower that comprised 15 different republics and a complex bureaucratic system with substantial state capacity. To enforce order over 22 million square kilometres, the USSR had a military with over 5 million members, a sophisticated nuclear arsenal and it spent upwards of 25% of its GDP on defence through a planned war mobilisation economy. Not only was the USSR one of the more powerful empires in all of human history, but it was home to around 35 different national groups (Sakwa 1990: 233). By the end of 1991, collapse was imminent due to several processes, one of which was driven by national groups that demanded and successfully achieved territorial and governmental independence (Beissinger 2002; 2009). The breaking apart of this governance superstructure into more than a dozen separate states has since received significant interdisciplinary scholarly attention. To date, there have been hundreds of articles and dozens of books written on the topic of the Soviet collapse in multiple languages. However, our understanding of how military actors behaved in the face of territorial disintegration, mass rebellion and political power grabs remains underdeveloped.

While attention has been cast on military defection and its relation to regime transition and democratisation in the Arab Spring, we lack understanding of how armed forces behaved during one of the most significant periods of the twentieth century. This study puts forward the first analysis of military defection(s) that arose during the collapse of the USSR. Defection involves military actors that abrogate a basic commitment to defend their principal, fail to carry out orders or not report to duty (Brooks 2017; 2019). The phenomenon of defection represents an occurrence of insubordination on the part of senior or junior military members or security forces. Insubordination can take form as direct defiance of orders or through indirect defiance such as not doing or showing up for one’s job to protect a political status quo (Anisin 2020). Military personnel are not unified actors, and can engage in different types of defections according to the actor as well as the institutional context under attention (Albrecht & Ohl 2016: 41). A considerable literature has been concerned with observable avenues that incumbent regimes go down in order to prevent the occurrence of defection in times of political stability (Lee 2005; McLauchlin 2010; Pilster & Böhmelt 2011; Pion-Berlin et al. 2012; Makara 2013; Nepstad 2013; Geddes et al. 2014; Bou Nassif 2015; Johnson 2017; Anisin & Ayan Musil 2021; Kalin, Lounsbery & Pearson 2022). Similarly, civil resistance scholars have emphasised that the strategies waged by civilians have much to do with the conditions under which defection occurs (Sharp 2005; Nepstad 2013; Sutton et al. 2014; Degaut 2017; Croissant et al. 2018; Anisin 2020).

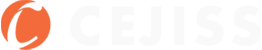

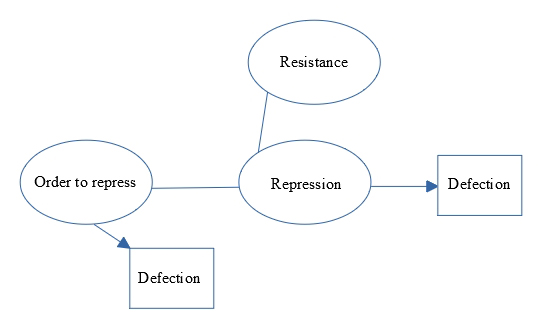

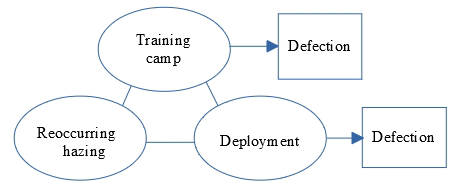

The downfall of the Soviet regime and its disintegration into 15 national states presents us with a fascinating but complex context in which to examine defection and its determinants. To date, data on this particular historical context have been underdeveloped and troubled by missing values. Only a few instances of defection in the context of the Soviet collapse have been observed in both comparative and quantitative literature on defection and in specific historical research on this time period. This study fills these gaps. First, it identifies the extent to which defections arose during the Soviet collapse according to republic and actor type. Second, it adds to scholarship on the nature of defection through identifying the different pathways that can bring about this outcome. The results of this study reveal that defections were brought about by multiple pathways and mechanisms. Pathway one features civil resistance and repression in which officers, soldiers and conscripts defected either before being ordered to repress civilians or after repressive acts were carried out. The second identified pathway features the waging of a coup-attempt by commanders, whereas pathway three features defection by conscripts which took place in the late 1980s as a result of severe forms of hazing and ethnic antagonisms. The fourth pathway features defections that arose from territorial disintegration alongside national independence movements in which military members rejected serving prior principals.

The order of this study is as follows: an overview of the historical time period under attention is provided followed by a section that identifies the gaps in knowledge that currently exist on defection during the Soviet collapse. A research design section then lays out this study’s comparative approach and describes underlying theoretical assumptions as well as variables that surround the phenomenon of defection. This is complemented by a description of Soviet civil-military relations including an explanation of the complexity of ethnic dynamics that underpinned the Soviet Armed Forces. Afterwards, a comparative investigation is carried out. Four total pathways are identified to have brought about defection during the Soviet collapse. The pathways are complemented by an assessment of specific republics. Concluding segments of this study relate these findings to scholarship on this time period of history, on the nature of the phenomenon of defection, and propose directions for future social inquiry.

Investigating defection during the fall of the Soviet Union Investigating defection during the fall of the Soviet Union

The ending years of the USSR represent a difficult empirical realm in which to engage in comparative inquiry due to its territorial vastness, the diversity of the people that lived within the 15 republics and due to the significant degree of contingency that marked this period of political history. There is no single criterion that can accommodate all characteristics of the fall of the USSR (Karklins 1994, p. 29). While there are many different interesting and arguably unique components of the Soviet system, its economy warrants preliminary consideration. The USSR had a war-economy that dated to the 1920s. Its armament industry was not only confined to conflict endeavours but it covered nearly all socio-economic conditions and industries. The war-economy was the entire material and technical basis of the Soviet labour pool. It directed the state’s allocation and dealing of fiscal resources and encompassed sectors such as transportation, communication industries, public health, education, science and even culture (Checinski 1989, p. 207). By the 1980s, economic stagnation was a leading problem and a reformist debate was emerging in the Soviet Armed Forces. Some believed that the fundamental components of the Soviet economic system had to be altered. As Kass and Boli (1990) point out, ‘the High Command supported Gorbachev’s restructuring agenda precisely because it responded to the military’s long-standing concerns. Perestroika promised to deliver what the military needed: a modern economy, capable of producing the requisite quantity and quality of high-tech weaponry, and a healthy society, able to produce educated, fit, and motivated citizens to man the new weapons’ (Kass & Boli 1990: 390).

In conjunction with failure in the Afghan conflict, exceedingly poor conditions for soldiers and conscripts, and a general lack of morale, there was significant political pressure being aimed at the armed forces. Ideas on establishing a volunteer-only professional army were gaining prominence as was the notion that each republic should have its own national army. Another salient proposal was for military units to be newly established based on national minorities (Arnett & Fitzgerald 1990: 193). Those that advocated the latter idea of national formations did so due to concerns coming from various republics that wanted independence from the Soviet Union – such as Moldova, Armenia, Georgia and the Baltic states (Arnett & Fitzgerald 1990: 198). High ranking military leaders, however, starkly opposed reform (Raevsky 1993). Those who sought to reform the military emphasised that corruption, stagnation and patronage in the armed forces were contingent on the secrecy of the Soviet system itself which allowed and even permitted military commanders to exploit their subordinates (Vallance 1994). On top of these issues and accompanying debates, pressure from mobilised segments of society was significant as dissent was present in nearly all of the Soviet Republics by the end of 1989. From February 1988 through to August 1991, an average of one million people participated each month over ethno-nationalist issues in the republics (Beissinger 2010: 106). In December 1988 Gorbachev announced reduction of the armed forces by 500,000 men.

Literature on the Soviet collapse falls into two categories, with the first being national identity and the second institutional decay and change (Barnes 2014). Mobilisation during the collapse of the USSR was widespread. Mass mobilisation campaigns in numerous republics had significant effects on one another in a grander course of action based around national sovereignty (Beissinger 2002). The greatest degrees of mobilisation were observed in areas of republics that were socially and economically developed and those with concentrated urban populations (Emizet & Hesli 1995). In contrast, Dallin (1992) points out that glasnost and the state-led project of democratisation were of great significance to stirring both discontent and opportunity in the republics. The formation of new unofficial organisations in 1988 was the moment in which the Soviet regime ‘ceased to be totalitarian’, argues Karklin (1994: 38). Some scholars, such as Brubaker (1994), contend that institutionally empowered elites of the national republics had the biggest roles in bringing the USSR into disintegration (Brubaker 1994: 60-61).

It is expected that significant focus has hitherto been placed on the coup attempt as this was a turning point in history, yet this has left a substantial gap in our knowledge when it comes to the other republics of the Soviet Union. How did military forces behave during the disintegration of the USSR? Apart from the coup attempt, were there any other defections? If so, what actors or groups defected, and how did they defect? Answers to these questions cannot be found in a diverse literature on the Soviet collapse. Similar issues are evident in popularly utilised data on civil resistance. The table below highlights these significant gaps in knowledge on defection during this time period. Data are drawn from the NAVCO 2.0 (Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes Data Project) which has been widely utilised by scholars and is among the only data sets that contain observations on both oppositional campaigns that challenged status quos during the Soviet collapse as well as the outcome of security force defection. Here, defection is defined as ‘the regime loses support from the military and/or security forces through major defections or loyalty shifts’ (Chenoweth & Lewis 2013).

As subsequent sections of this study will reveal, a number of the republics listed above that NAVCO 2.0 labels as having experienced no defections actually did experience defections. More significantly, 8 out of the 15 republics listed above are not included in the data at all. There was a significant amount of dissent that arose throughout most republics (Beissinger 2009), but the data do not capture these observations. From January 1988 to January 1989, three to eight million people dissented across the republics (Beissinger 2002). Second to this period, from June 1989 to July 1990 there were one to four and a half million dissidents per month on average (Beissinger 2002: 105). The data shown in Table 1 accurately highlight the lack of scholarly attention that has been given to the Soviet collapse in quantitative and comparative inquiry. This study adopts a comparative approach to investigate these processes across 15 Soviet republics during the union’s collapse.

Table 1. Commonly used data on defection

|

|

|

|

|

| 1. Lithuania | Sajudis, Pro-dem movement (1989-91) | Nonviolent | None |

| 2. Latvia | Pro-dem movement (1989-91) | Nonviolent | None |

| 3. Georgia | Gamsakhurdia & Abkhazia (1988-93) | Violent | Yes, 1992 |

| 4. Estonia | Singing Revolution (1987-91) | Nonviolent | None |

| 5. Ukraine | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 6. Belarus | Anti-communist movement (1988-91) | Nonviolent | None |

| 7. Moldova | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 8. Azerbaijan | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 9. Uzbekistan | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 10. Kyrgyzstan | Pro-dem movement (1990-91) | Nonviolent | None |

| 11. Tajikistan | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 12. Armenia | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 13. Turkmenistan | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 14. Kazakhstan | Not included in data | n/a | n/a |

| 15. Russia | Pro-dem movement (1990-91) | Nonviolent | Yes, 1991 |

Source: Data drawn from NAVCO 2.0 (Chenoweth & Lewis, 2013)

Research design

In the contexts under attention, defection either did occur or did not occur across all Soviet republics which indicates variance in the dependent variable. There were also different actors who either did or did not defect. Likewise, there is variation between different republics, the degrees of mobilisation they experienced as well as the interactions that took place between armed forces and opposition. On the other hand, there is no variance in the types of governmental systems that formulated the 15 republics under attention – all were communist systems and were integrated into the USSR’s planned war mobilisation economy. The dependent variable is classified based on a two-fold definition of defection (which will enable the results of this study to be integrated into commonly used data on this topic). First, defection is defined in the NAVCO 2.0 data: ‘the regime loses support from the military and/or security forces through major defections or loyalty shifts’ (Chenoweth & Lewis 2013: 8). Second, Albrecht and Ohl’s (2016) categorisation of military actor types is drawn on. A given incumbent principal’s orders will either be met by commander resistance (failure to carry out the order) or commander loyalty (agreement). Contingent upon one of these two choices, subordinates (lower ranking military agents) will then either: 1) exit – defect, or: 2) resist their orders – defect; or 3) remain loyal – carry out the order.

Considering that the Soviet context featured different republics and ethnicities, and that a heterogeneous collection of events occurred during its downfall, this analysis is not limited to only contextual circumstances featuring resistance and repression. Defection is observed on a case-by-case basis across different situations. Our comparative approach enables this study to account for equifinality which is a critical feature of multiple case study methodology (Goertz 2017: 52). Equifinality means a given outcome or phenomenon of interest has emerged across different cases through a different set of independent variables and pathways (George and Bennett 2005: 157). These are important dynamics to consider for our understanding of causation because equifinality entails there may exist not only multiple causal mechanisms that contribute to the occurrence of a given outcome, but there may also exist multiple pathways that bring it about (Geortz 2017: 53). For example, subordinates (including conscripts), can defect from their principal(s) due to different mechanisms which ultimately bring about an identical outcome of defection. Along similar lines, in the context of protest and mass mobilisation, the reason behind why civil resistance is not the only condition or ‘master variable’ that is responsible for aggregate increases in defection is because of equifinality – different patterns can lead to similar outcomes. As subsequent sections will reveal, defections occurred during the Soviet collapse throughout contexts in which mobilisation was not the determinative factor.

We now turn to the qualitative characteristics that formulated civil-military relations and security institutions throughout the USSR. Once these characteristics are described and categorised, we then will shift to the ethnic relations within the armed forces in the USSR followed by factors that have been found to be causally related to the outcome of defection in scholarship.

Characteristics and the extent of defections throughout Soviet Republics

Soviet civil-military relations

The Soviet Army was under control of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the most powerful political position. The General Staff of the Soviet Army was the main defence and planning organ of the Ministry of Defense (Betz 2004: 22). The Soviet Army included Ground Forces, Air Forces, Air Defence Forces, Strategic Rocket Forces and the Navy. On the other hand, security agencies such as the Committee for State Security (KGB) and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) also had significant power in internal security as well as in safeguarding the Kremlin (Taylor 2003: 199). The KGB possessed around 250,000 members, whereas the MVD had around 350,000 internal troops (Odom 1998: 33). Patronage systems within the Soviet military were used for promotion and position assignment preferences (Raevsky 1993: 536; Vallance 1994: 704). The hierarchies of the Communist Party (CP) entailed that different functions and relationships existed between not only party and military, but also between military and society. This makes it difficult to observe these relationships as a single unit of analysis (Hough 1969). Nevertheless, certain periods Soviet history did possess particular consistencies between armed forces and civilian leadership. Some historians argue that throughout the duration of the USSR’s existence, there were significant organisational ‘structure barriers’ that stood in the way of military intervention in civil affairs (Taylor 2003: 201).

The Soviet Armed Forces were based on a unitary configuration that was divided territorially into military districts; while the military structure was comprised of professional military (officer corps) and enlisted personnel (conscripts). The ethnic composition of units did not depend upon their location due to an exterritorial recruiting concept. Officer schools were entered by educated male youth from all the republics after passing a security filter of a KGB check. On the other hand, the security force structure was also the same for all the republics — featuring both the police force (MVD) and secret political police (KGB). In the field, officers of the MVD and KGB were recruited from local ethnic groups, while senior leadership was appointed after approval from Moscow headquarters. Apart from the 1991 coup attempt, the armed forces were apolitical throughout the post-Stalinist era. For example, Gorbachev’s climb to the top leadership position in the CP was made possible by the inner circle of the CP, and the armed forces played ‘absolutely no role’ in his egress (Taylor 2003: 197).

Conscription and ethnic makeup

During the historical formation of the Soviet Union, in the 1920s, 15 republics were founded through nation-building processes in which a Soviet ‘people’ (narod) were constructed (Isaacs & Polese 2015). There were many ethnic groups and nationalities who served for the USSR, and from the outset of the establishment of the republics, linguistic and cultural autonomy were granted to populations (Terry 1998). For example, at the height of WWII, infantry units in the armed forces were comprised of Russians (62.95%), Ukrainians (14.52%), Belarussians (1.9%), Uzbeks (2.88%), Tartars (2.38%), Kazakhs (2.4%), Jews (1.42%), Azerbaijanis (1.55%), Georgians (1.5%), Armenians (1.51%), Mordvinians (0.79%), Chuvash (0.75%), Tadzhiks (0.48%), Kirghiz (0.57%), Bashkirs (0.5%), Peoples of Dagestan (0.18%), Turkmen (0.47%), Udmurts (0.26%), Chechen-Ingush (0.004%), Mari (0.26%), Komi (0.16), Osetins (0.16%), Karelians (0.09%), Kabardino-Balkars (0.06), Kalmyks (0.08%), Moldovans (0.04%) and Baltic peoples [Latvian, Estonian, Lithuanian] (0.5%) (Blauvelt 2003: 54). By the late 1980s, Slavic troops still made up a substantial majority of all armed forces members. In detail, in 1990, 69.2% of all military members were ethnic Slavic (Russian, Ukrainian, Belorussian), 1.9% were Baltic people, 20.6% were Muslim-Turkic people and 8.3% were all other types of people (Alexiev & Wimbush 1988).

Moscow strategically created institutions for each national territory that were led by their own ethnic elites who were aligned with communist policy preferences. Although Marxist theory and Leninist principles entail that ethnicity and nationalism are bourgeois conditions that present obstacles to revolutionary consciousness, the large number of national minorities were somewhat of a nuisance for Soviet Bolshevik leadership (Blauvelt 2003: 47). Ethnic dynamics did not end up interfering with the greater ideological purpose of articulating an idea and identity of a Soviet proletariat and they did not weaken the USSR during the Nazi invasion of its territory in WWII. They did, however, play a major role during the Soviet collapse. All men were mandatory conscripts to the Soviet Army from the age of 18. Once in the military, conscripts would be purposely disconnected from their homes and civilian social groups – hence they would serve in varying areas throughout the USSR (Lehrke 2013). The Soviet Army reflected the immense diverse ethnic composition of the country, but it also reflected stereotypes and contained intentional policies of discrimination (Daugherty 1994: 172). Conscription was not a straightforward and equal process for all civilians in the Soviet Union. Any Central Asian, Transcaucasian, Latvian, Estonian, Lithuanian or Jewish man would face discrimination in the process of assignment via ethnic, educational and physical profiling (Daugherty 1994: 178).

Ethnic minorities did not get assigned to positions that required the managing of sophisticated equipment, as they were largely in the construction, repairing and building segments of the military (Daugherty 1994: 179). Soviet leadership also took the historical reliability of troops from Central Asia and Transcaucasia into consideration when forming its promotion and recruitment policies. Lack of reliability of troops from these regions was prevalent in Tsarist times and throughout the existence of the Soviet Union. For example, an ethnic-Georgian unit was dispatched to respond to protesters in Tbilisi in 1956, but the troops did not open fire on their native countrymen, even under orders to do so from higher ranking officers (ethnic Russians) (Daugherty 1994: 167). As such, it is plausible to make the general claim that ethnic differences in the Soviet Army were significant. Around 90 percent of the officer corps was Slavic (Taylor 2003: 214). Of the three Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), ethnic Russians were a minority population in Lithuania even though they comprised the same percentage of citizens in Lithuania as did ethnic Polish (8 percent), yet their numbers in the armed forces were greater than of citizens from those respective republics. The same characteristics were present in other neighbouring republics such as in Moldova (Scott & Scott 1979). This enabled higher ranked military actors to have significant agreement with one another throughout established hierarchies. Such practices paved the way for later adversities including rifts, inequality and cleavages between non-ethnic Russians and ethnic Russians throughout the lower ranks of the armed forces.

Characteristics surrounding defection

The following variables are drawn from literature on defection. These are factors that scholars in both civil-military relations and civil resistance literatures have identified as antecedent characteristics that surround the outcome of interest. The following variables are drawn from literature on defection. These are factors that scholars in both civil-military relations and civil resistance literatures have identified as antecedent characteristics that surround the outcome of interest.

First, regime fragility differs from state fragility which has been utilised to measure how much capacity governments have across social, economic and political indicators or has been drawn on via the World Bank’s low-income countries under stress categorisation (Simpson & Hawkins 2018: 2-23). The Soviet Union possessed significant governmental capacity that functioned largely through its war mobilisation economy, but towards the latter half of the 1980s, regime fragility arose while state capacity remained robust. Regime fragility has to do with both citizen and elite level perceptions of the status and stability of the incumbent government. A low level of regime fragility would be attributed to the USSR in the 1960s or 70s – both were decades in which political power was consolidated, perceptions of the standing of the incumbent regime were positive, political opposition was nearly absent and cultural and international standings of the regime were optimistic. A medium level of regime fragility was present throughout the Stalinist purges of the 1930s and the period of WWII in the 1940s. In contrast, the 1980s were marked by a high level of regime fragility. Perestroika and glasnost led to a newfound contingency in Soviet structure that had yet to be seen or even imagined in that point of historical time. There was also a significant economic downturn that fostered significant debate around the direction of the Soviet system and its sustainability. In conjunction, a failed military operation in Afghanistan contributed to decisions to reduce governmental spending including cutting down the whopping 25% GDP that was spent on defence. On top of all of these newly arisen forces, 1989 saw nearly all Warsaw Pact allied states experience successful pro-democracy revolutions including East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria and Romania.

Second, the variable of mobilisation captures degrees of collective action that were waged against status quos. High dissent entails an opposition movement that numbered in the millions. Low dissent entails small oppositional campaigns numbering in the thousands whereas a medium threshold entails collective action in the tens of thousands. For example, dissent in the Central Asian republics was substantially less than in Transcaucasia. In the Central Asian republics, there was a lack of popular nationalist movements, and hence, when the Soviet Union formally collapsed in 1991, the Central Asian republics were ‘reluctantly’ shifted into being independent states (Merry 2004). In some regions of the republics, such as in Eastern Ukraine and Northern Kazakhstan, ethnic-Russian coal miners were prominently active in protest. As noted by Beissinger (2002: 398), ‘Outside of highly Russified regions such as Donbass, northern Kazakhstan, and Belorussia, nationalism trumped class as the most significant frame for mobilisation in the non-Russian republics.’ In January of 1991, upwards of one million participants demonstrated throughout only Russia.

Third, the variable of military-society ethnicity captures the makeup of the armed forces in relation to the societies that its members stem to. Estimates indicate that in 1985, there were a total of 195 million Slavs in the Soviet Union (142 million Russians, 42 million Ukrainians, 9.5 million Belarussians); 5 million Baltic people; 53 million Muslim-Turkic people; and 23 million of all others (Armenians, Georgians, Jews, Moldovans) (Daugherty 1994: 181). Ethnic Russians made up more than a majority of the armed forces that were stationed across all 15 republics. As such, observable rifts existed between Latvians, Estonians and Lithuanians with relation to ethnic Russians in the Soviet Army (Daugherty 1994: 172).

Fourth, the Soviet Armed Forces were counterbalanced to a significant extent. The greater purpose of the KGB was counter-intelligence and special intelligence pertaining to political dissent, whereas the MVD’s purpose was to manage internal affairs. While some scholars have argued that both bodies simply could not counterbalance the armed forces due to their strategic positions and roles in the structure of the Soviet communist system (Knight 1990), such viewpoints are in the minority. Most scholars believe the KGB did monitor the political attitudes of military agents, specifically through its Third Chief Directorate. This was a counter-intelligence and political surveillance division of the KGB that oversaw the entire armed forces (Sever 2008). Several specific units such as the 27th motorised rifle brigade and the Internal Troops (Vnutrenniye Voyska) of the MVD served as counterweights to army intervention (Taylor 2003: 212).

Table 2. Pathways towards defection during the Soviet collapse

| Republic | Pathway(s) | Defector(s) |

| 1. Lithuania | Pathways, (1) Resistance / Repression; (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 2. Latvia | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 3. Georgia | Pathways, (1) Resistance / Repression; (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 4. Estonia | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Commander; Subordinates |

| 5. Ukraine | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Commanders; Subordinates |

| 6. Belarus | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance | Subordinates |

| 7. Moldova | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 8. Azerbaijan | Pathways, (1) Resistance / Repression; (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 9. Uzbekistan | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 10. Kyrgyzstan | None | |

| 11. Tajikistan | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 12. Armenia | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 13. Turkmenistan | Pathways, (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Subordinates |

| 14. Kazakhstan | None | |

| 15. Russia | Pathways, (1) Resistance / Repression; (2) Coup; (3) Hazing / Draft Non-compliance; (4) Territorial Disintegration | Commanders; Subordinates |

*Pathway 1 – Resistance and Repression; *Pathway 2 – Waging a Coup; *Pathway 3 – Hazing and Draft Non-compliance; *Pathway 4 – Territorial Disintegration

Source: Data drawn from author’s work based on qualitative inquiry into each republic

These four variables were either present or absent across the cases under attention – Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia, Estonia, Ukraine, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Russia had the following characteristics: all contexts experienced high levels of regime fragility during the Soviet collapse. In terms of mobilisation all countries had high rates apart from Belarus (low), Kyrgyzstan (low), Kazakhstan (low) and Moldova (medium). In terms of military-society ethnic relations in each country, all had a majority of Russian ethnic members serving in the armed forces. Likewise, all republics had high levels of counterbalancing through the presence of the KGB and MVD.These four variables were either present or absent across the cases under attention – Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia, Estonia, Ukraine, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Russia had the following characteristics: all contexts experienced high levels of regime fragility during the Soviet collapse. In terms of mobilisation all countries had high rates apart from Belarus (low), Kyrgyzstan (low), Kazakhstan (low) and Moldova (medium). In terms of military-society ethnic relations in each country, all had a majority of Russian ethnic members serving in the armed forces. Likewise, all republics had high levels of counterbalancing through the presence of the KGB and MVD.

Below, results from empirical analysis of the 15 cases reveal that four different pathways resulted in defections during the period of the Soviet collapse. Table 2 includes the specific characteristics of defection that each republic experienced according to pathway and actor type. These results contain the first documentation of defections that either arose or did not arise across the Soviet republics. The subsequent section visualises the conceptual nature of these four pathways and is complemented by qualitative case specific analyses.

In light of the lack of knowledge that currently exists (see Table 1) on this topic as observed in quantitative research on conflict and protest outcomes, the results in Table 2 reveal that in the context of the collapse of the USSR, a significant number of empirical outcomes occurred but have yet to be identified and documented. Defections occurred first in 1989 by subordinates (officers and conscripts) and reoccurred until late 1991 in different temporal circumstances and pathways. In total, 13 out of 15 republics experienced subordinate defection – whereas 3 out of 15 experienced commander defections. Before delving into specific cases, it is important to list the republics that did not experience defections. No defections took place in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The Strategic Rocket Forces (SRF) were deployed in Kazakhstan – these included intercontinental ballistic missile systems (Odom 1998: 300). Kyrgyzstan, in contrast, hosted one of the more prestigious pilot training schools for the Air Force. As Odom notes, the SRF did not experience the same rapid deterioration as other branches of forces (Odom 1998: 303). Furthermore, events that arose in 1988 served as a catalyst for numerous instances of defection across 13 republics. An ethnic and territorial dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh broke out into armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Upwards of 20,000 Soviet troops entered the Azerbaijani capital Baku in January 1990 – leading to a significant number of civilian casualties. Across nearly all 15 republics, actions of exiting and resisting orders were widespread.

Pathways to defection throughout the Soviet republics

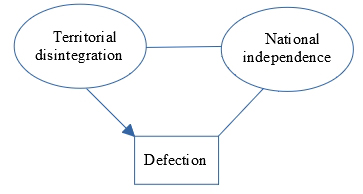

Along with identifying instances of defection, visualising and conceptualising their spatial and temporal characteristics can help to make sense of the empirical phenomenon of defection – a phenomenon that is causally complex (non-linear) and equifinal (multifaceted) in its nature. The most common pathways observable across cases are pathways three and four – widespread draft resistance along with territorial disintegration were significant across nearly all republics. Figure 1 below (and Figure 2 on subsequent pages) help to visualise these four pathways.

Figure 1. Pathways one (resistance and repression) and two (coup)

Pathway one – Resistance and repression [officers, soldiers and conscripts defect either before being ordered to repress civilians or after repressive acts are carried out]

Pathway Two – Waging a coup d’état [Commanders and in some cases, subordinates, defect in attempt to overthrow the incumbent government]

Pathway one – Resistance and repression [officers, soldiers and conscripts defect either before being ordered to repress civilians or after repressive acts are carried out]

Tbilisi, Georgia: Dissidents in Georgia organised a mass resistance movement in an attempt to rid their republic of communist governance and achieve full independence from Moscow (Zhirokhov 2012: 315). A massacre occurred on 9 April 1989 – MVD troops and military units dispersed a meeting which led to 19 fatalities. The Tbilisi massacre was a highly significant turning point that negatively impacted the morale of the Soviet Army, and also shifted public consciousness about communist governments (Hosking 1991). Taylor (2003) describes the fallout from this massacre as being psychologically detrimental to the institutional basis and public standing of the armed forces. Blame was cast on the armed forces for the events in Tbilisi which led to the ‘Tbilisi Syndrome’ – an adverse psychological development that caused hesitation about military involvement in the internal context of the USSR (Taylor 2003: 223). Publicly, Gorbachev and the Kremlin refused to acknowledge their role in ordering the Soviet Army to use violence against demonstrations. This further exacerbated an already impeding problem that the military was facing – blame. Society increasingly blamed the army and extraordinary amounts of defence spending for the Soviet Union’s economic hardships (Lehrke 2013: 90). Tbilisi fostered public outrage and escalated calls for radical democratisation (Karklin 1994: 36). From this point on, both ethnic soldiers and Slavic soldiers in the Soviet Army engaged in resistance to future orders, while others exited their positions altogether. Gorbachev’s specific orders to attempt to settle unrest led to the refusal of minorities to serve in the Soviet Army (Reese 2002: 172). Tbilisi, Georgia: Dissidents in Georgia organised a mass resistance movement in an attempt to rid their republic of communist governance and achieve full independence from Moscow (Zhirokhov 2012: 315). A massacre occurred on 9 April 1989 – MVD troops and military units dispersed a meeting which led to 19 fatalities. The Tbilisi massacre was a highly significant turning point that negatively impacted the morale of the Soviet Army, and also shifted public consciousness about communist governments (Hosking 1991). Taylor (2003) describes the fallout from this massacre as being psychologically detrimental to the institutional basis and public standing of the armed forces. Blame was cast on the armed forces for the events in Tbilisi which led to the ‘Tbilisi Syndrome’ – an adverse psychological development that caused hesitation about military involvement in the internal context of the USSR (Taylor 2003: 223). Publicly, Gorbachev and the Kremlin refused to acknowledge their role in ordering the Soviet Army to use violence against demonstrations. This further exacerbated an already impeding problem that the military was facing – blame. Society increasingly blamed the army and extraordinary amounts of defence spending for the Soviet Union’s economic hardships (Lehrke 2013: 90). Tbilisi fostered public outrage and escalated calls for radical democratisation (Karklin 1994: 36). From this point on, both ethnic soldiers and Slavic soldiers in the Soviet Army engaged in resistance to future orders, while others exited their positions altogether. Gorbachev’s specific orders to attempt to settle unrest led to the refusal of minorities to serve in the Soviet Army (Reese 2002: 172).

After the events in Tbilisi, high ranking generals (commanders) defected from the CPSU and pursued their own political interests. Although joining political movements was technically not illegal under Soviet law, this still qualifies as a form of defection because the allegiance that given actors shifted, which falls under the definition of defection used in this study. Along these lines, over the course of less than one year, right-wing or hard-line generals created extra-party organisations such as ‘Soyuz’ which sought to stop the disintegration of the USSR. A General by the name of Volkogonov in contrast, joined a liberal political movement - ‘For Democratic Reforms’ (Barany 1993: 16).

Baku, Azerbaijan: Regular acts of repression and repeated states of emergency ‘lost much of their dampening effects on dissent after mid-1989’ (Beissinger 2002: 371). To make matters worse for Moscow, by summer of 1989, violent ethno-religious conflicts broke out in the southern USSR in Azerbaijan. Gorbachev’s orders to send in the Soviet Army in the years of 1989-90 resulted in its eventual death and destruction (Sultanov 2004: 118). Specifically, in January 1990, the Soviet army, its Black Sea fleet and KGB special forces clashed with civilians which led to upwards of 100 civilian fatalities and around 20-30 soldier fatalities (Kushen 1991). The Soviet government notified the UN that it had called a state of emergency in Baku (as per guidelines of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights), but it did not call a state of emergency in the cities of Lenkoran, Neftechala and among others in which Soviet soldiers killed civilians (Kushen 1991: 10). The fallout from these events was substantial. Defections that occurred in 1989 were enacted not only by ethnic minorities in the Soviet Army, but also by ethnic Slavs that formed the greater majority of its personnel. In the latter scenario, defection and resistance of ethnic-Slavic members of the Soviet Army was heavily propelled by newly formed domestic NGO groups such as ‘Mothers for Soldiers’ who became highly active in the Baltic republics, Ukraine, regional Russian cities and in Uzbekistan. Such organisations gained prominence due to persistent domestic upheavals, the dangers associated with responding to those upheavals for soldiers and conflicts, as well as a newfound uncertainty surrounding the integrity of military service. Even Gorbachev appointed a Presidential commission to investigate noncombat deaths across military units (Solnick 1999: 205). What later became known as ‘Black January’, led to the secession of Azerbaijan from the USSR in the first ranks.

Vilnius, Lithuania: In 1991, the final nail went into the Politburo’s coffin. Events in 1991 Vilnius exacerbated an already salient problem in the USSR. In March of 1990, the Lithuanian parliament had voted for a restoration of pre-Vilnius, Lithuania: In 1991, the final nail went into the Politburo’s coffin. Events in 1991 Vilnius exacerbated an already salient problem in the USSR. In March of 1990, the Lithuanian parliament had voted for a restoration of pre--WWII independence, which essentially was the first step in ridding the country of its long stemming communist institutions. The Soviet government continuously sent paratroopers into Vilnius for the duration of the year, and in the face of January of 1991, paratroopers killed 14 unarmed protesters and wounded 200 (Sharp 2005: 281). These events led to Lithuanians receiving solidarity from other republics who also sought to undermine the Soviet regime. More than 64 different demonstrations arose in response to the events at Vilnius in Russia, Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova (Beissinger 2002: 380). In an analysis of the Vilnius events, Russian historians asked in 1991, [translation from Russian] ‘I am interested, in his view, does Gorbachev thinks he is now in control of the situation? Are the army, MVD and KGB still under his control? The latest events in the Baltics make me doubt this is so’ (Moroz 2011: 441). Events in the Baltics signalled that mass civilian demonstrations could deter armed units and can make soldiers back down from orders of repression – both dynamics re-emerged in the 1991 coup attempt (Karklin 1994: 37).

Another fascinating case can be observed in the context of Estonia. Here, Dzhokhar Dudayev (among the only non-ethnic Russian generals and commander of strategic nuclear units), refused orders from Moscow to shut down Estonian media networks in 1989 (Cornell 2005:195). Sympathetic to Estonian national independence claims, Seely (2012) describes Dudayev as a ‘closet supporter’ of the movement who learned from it and took revolutionary insights with him back to his native area of Chechnya. In the span of one year (1989-1990), the aforementioned dramatic events occurred as Soviet troops stormed into Vilnius. Afterwards, there were plans to go to Tallin and at this point in time, Boris Yeltsin attempted to fly into Tallin in an effort to de-escalate the situation (Seely 2012). As this was occurring, Dudayev went on the national radio of Estonia and stated that as commander of the Tartu Air Division, he would not permit Soviet troops to come through the republic’s air space. As a supporter of Yeltsin, Dudayev then permitted him to enter the republic via automobile. Yeltsin would go on to be a key actor in an event that we will now turn to, an event that led to the formal collapse of the USSR, the August Coup attempt.

Pathway Two – Waging a Coup d’état [Commanders and in some cases, subordinates, defect in attempt to overthrow the incumbent government]

August 1991, Coup Attempt: By late summer of 1991, high ranking actors (e.g., Dmitry Yazov; Mikhail Moiseyev; Pavel Grachev; Valentin Varennikov; Vladimir Chernavin; Vladimir Kryuchkov, among others) from the Soviet Army, KGB and MVD grew increasingly displeased with Gorbachev’s actions. These actors viewed Gorbachev’s response to national independence movements in the republics as a contradictory mixture of sanctions and threats and negotiations, and hence, members of the high command urged harsher measures if Gorbachev failed to act on their recommendations (Brusster & Jones 1995: 8). In July, Boris Gromov (ground forces commander and first deputy chief of the Internal Ministry) issued a ‘Word to the People’ along with other conservative actors in order to halt the disintegration of the USSR (Brusster & Jones 1995: 12). Meanwhile, as described by Brusster and Jones (1995) many officers had completely opposite viewpoints and became active in republic legislatures while simultaneously aligning themselves with reformist groups. This resulted in a deeply divided military and both ends of the political spectrum were involved in reformist political groups (Brusster & Jones 1995: 12). Just days before Gorbachev was set to negotiate a new Union treaty with republics that was intended to give them sovereignty status, the August coup attempt was launched. Known as the great ‘Putsch’, hardliner insiders initiated the putsch with the aim to hold back reforms and retain state power (Lehrke 2013: 98).

As tanks rolled into the centre of Moscow, a plan was launched to attack the Russian White House (Brusster & Jones 1995: 14). On the night of 20 August, mass crowds surrounded the White House and, in response, the following morning Yazov and Kryuchkov withdrew the troops. Throughout these quick and contingent events, when orders were given by commanders, subordinates did not respond to instructions of repression (Smith 2002: 30). Some of the units even defected to Boris Yeltsin’s side. Historians generally agree that the military was divided over the coup, and that the precedent of non-interference into civilian affairs that the Soviet army was accustomed to ended up preventing subordinates from carrying out their orders. Another dynamic has to do with the ethnic--Russian dominated officer corps being unwilling to use force against other Russians, in the specific context of the Moscow city centre (Odom 1998: 466). The failed coup also illustrates how a different set of mechanisms that drove defection – based around a power struggle that arose during a period of immense regime fragility. Whereas the first pathway we observed features repression and mobilisation with commanders giving orders and subordinates either defecting from orders or defecting after carrying them out, this pathway specifically saw commanders breaking away from their principal(s) and then subordinates failing to carry out commander orders.

Finally, the impact of the failed coup attempt had dramatic consequences for the republic of Ukraine where there were not only more senior military commanders than in any other republic apart from Russia, but the great majority of senior military commanders at the time had opposed the creation of an independent Ukrainian armed forces (UAF) (Jaworsky 1996: 227). However, two senior members, Leonid Kravchuk and Kostiantyn Morozov put forward a determined effort to establish the UAF by December of 1991, which in part was made possible by the ‘dramatic developments which followed the August 1991 coup attempt and were unable to organise a coherent opposition to the creation of the UAF’ (Jaworsky 1996: 226).

Figure 2. Pathways three (hazing and draft non-compliance) and four (territorial disintegration)

Pathway three – Hazing [widespread practices of person-to-person brutality, racism and abuse arise in in settings of training as well as deployment – bringing about defection]

Pathway four – Territorial disintegration [as part of a national independence movement, commanders, subordinates including soldiers and conscripts will reject serving for a prior principal due to the prospect and desire to serve for a newly founded territorial or political organisation]

Pathway three – Hazing [widespread practices of person-to-person brutality, racism and abuse arise in in settings of training as well as deployment – bringing about defection]

Dedovchshina and Zemlyachestvo: To the best of my knowledge, there are no studies in the civil-military relations literature that link occurrences of widespread defection directly to hazing or bullying in a given country’s armed forces. In the Soviet context however, hazing turned out to be monumentally significant in discouraging both soldiers and conscripts from participating in military service in the late 1980s. Known in the Russian language as ‘dedovshchina’ - a unique form of hazing existed in the context of the Russian empire, was carried over to the Soviet Union and remained prevalent into the early 2000s in the Russian Federation. This was as Daugherty (1994) correctly describes it, a form of severe bullying that ended up being integral to and inseparable to the basic training processes dating back to Tsar Nicholas I. Dedovschina includes abuse of soldiers and conscripts such as sexual violence, beatings, bullying, confiscation of personal belongings, salaries and other adverse behaviour (Eichler 2011). During the late 1980s, Glasnost made public discussions of dedovshschina possible for the first time and a grim reality set in for parents who had sons that were either in the armed forces or in plan to be conscripted– young men that entered the army fit, healthy and with ambitions for a future career often returned to their parents as ‘corpses, murdered or hounded to suicide by the predators within their own ranks’ (Eaton 2004: 94). Dedovshchina was not a Slavic-on-Slavic or Slavic-on-ethnic minority practice. It was widespread throughout the armed forces, and ethnic groups, where possible, would bound together and carry out this hazing practice on individuals from other ethnic backgrounds.

In contrast to the hierarchical nature of dedovschina, zemlyachestvo refers to a historical concept in which an individual is said to belong to his/her place of origin whether it be a village, region or qualitative place of residence. In practice, zemlyachestvo resulted in regional bonding and would be used by ethnic groups in an attempt to combat the ill-effects of dedovschina. Zemlyachestvo resulted in the formation of networks of ‘regiment-level gangs’ that were designed to protect members from abuse (Spivak & Pridemore 2004: 35). Abuse often stemmed to the general practice of dedovschina along with the presence of ethnic antagonisms and racist components. As Spivak and Pridemore (2004) describe it, when ethnic minority soldiers were abused, their national comrades would band together and attempt to offer protection. Differences in language also exacerbated the already pre-existent problem of ethnic segregation within enlisted forces. Ethnic minority conscripts were often unable to communicate with their commanders and by the time the Afghan invasion occurred, these adversities resulted in violent clashes between different enlisted ranks and even led to the setting up of language camps for non-Russian conscripts (Solnick 1999: 183). In the late 1980s, sociologists observed that ethnic gags even arose within units which led to Baltic conscripts getting pinned against Russians or Russians against Transcaucasians or Central Asians (Solnick 1999: 184). In conjunction, the many different components of ethnic difference(s) contributed to an adverse spiral of outcomes. As a result of hazing, it is estimated up to 60-70% of all conscripts from non-Slavic republics refused their service orders in the late 1980s (Daucé & Sieca-Kozlowski 2006), which brings us to the fourth and final pathway.

Pathway four – Territorial disintegration [as part of a national independence movement, commanders, subordinates including soldiers and conscripts will reject serving for a prior principal due to the prospect and desire to serve for a newly founded territorial or political organisation]

Widespread Draft Non-compliance: Draft evasion in the 1960s and 70s was rare but not unheard of (Solnick 1999: 170), yet by the late 1980s, draft non--compliance became widespread – some estimates indicate that draft evasion increased eightfold from 1985 to 1990 (Cortright & Watts 1991: 166). Fowkes argues that, ‘the Soviet Army was under threat of dissolution from the moment that the nations decided to insist on their sovereignty’ (Fowkes 1999: 168). Solnick notes that, ‘In the late 1980s the undisputed authority of the Ministry of Defense over military manpower policy came into question. In effect, alternate principals emerged—newly elected parliaments at the all-Union and republican levels—asserting for the first time their constitutional right to set conscription policy independent of the defense ministry’(Solnick 1999: 176). What’s more, by 1990, noncombat deaths were at a historic high, 20 percent were brought about by suicide. There was no single process that led to widespread draft dodging, but rather, several factors undermined the overall draft including the demobilisation of students, reinterpretations of health deferrals and the defense ministry’s unsuccessful attempts to regain control over ‘renegade draft boards’ (Solnick 1999: 176). Additionally, many of the independence movements that arose in republics also called for conscripts to evade local drafts.

For instance, in Lithuania, 5000 men handed back their draft cards in February 1990 as a form of protest (Fowkes 1996: 169). In Georgia, hunger strikes and sit-ins were waged by draftees which led to widespread defiance and subsequent concessions from the Ministry of Defense which let Georgians serve only within their republic’s territory (Solnick 1999: 206). The Ministry of Defense ended up losing control over draft policies which in the context of Russia meant that other bodies, such as a committee of the USSR Supreme Soviet, articulated new guidelines for military reform which even included a first of its kind law that enabled conscientious objectors (as well as other objectors) to be registered (Solnick 1999: 205). On the ground, things were even grimmer. For the first time, the traditional Soviet conscription system became ineffective. From 1989 to 1990, draft reporting dropped in every single Soviet republic apart from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan; some drop-offs were colossal such as Armenia who experienced 100 percent of conscripts report for their draft in 1989 and only 22.5 percent the subsequent year. Estonia had a 79.5 percent rate of reporting in 1989 which dropped to only 35.9 percent in 1990. Similar drops can be observed in Latvia (90.7 to 39.5), Azerbaijan (97.8 to 84), Georgia (94.0 to 18.5), Lithuania (91.6 to 25.1), while most other republics experienced less (but still significant) drops such as Russia (100 to 95.4), Tajikistan (100 to 93), Moldova (100 to 96), Turkmenistan (100 to 96.1), Belorussia (100 to 90.4), Moldova (100 to 96), to the fewest changes in percentages as observed in Ukraine (97.6 to 95.1), Kazakhstan (100 to 100) and Kyrgyzstan (100 to 100) (Clark 2019). By April of 1991, the General Staff revealed that the military was short 135,000 men (Clark 2019). In non-Russian republics, new republic legislatures started to offer new guidelines that conflicted with those of the Military of Defense – which ultimately led to the former claiming ownership and power over local draft policy (Solnick 1999: 205).

Transcaucasia and the Baltic Republics: By gaining independence, republics simultaneously formalised their own citizens’ disservice from the Soviet Army through constructing new registration and enlistment regulations (Reese 2002: 176). The argument that many republics put forward to Moscow to justify the creation of their own armed forces was that it was a part of their sovereignty (Fowkes 1996: 169). Republics began to demand that their own conscripts refuse service outside of their territories and in an attempt to stop this process, on 1 December 1990 Gorbachev called such policies null and void. However, ‘it made no difference, they went on doing it’ (Fowkes 1996: 169). By the summer of 1991, over thirty laws or acts had been passed by republican parliaments or governments that interfered with the all-Union draft. Besides this drastic change in the status quo, the number of draft evaders was observed to have grown dramatically in the last years of the Soviet Union. Russian General Dmitrii Iazov noted that the army was short 400,000 soldiers due to their obstruction of conscription in 1990 (Reese 2002: 175). In July of 1990, the Ministry of Defense stated they were short of 536,000 men. By 1990, resistance to orders and military service grew to be so significant that all military units that were stationed in Transcaucasia were placed on a voluntary basis. The actions of officers and conscripts gave national separatists not only a concrete issue on which to base their social movements platform on, but it enabled them to quickly capture government positions in republics (Odom 1998: 297).

In the context of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Supreme Soviet declared its right to have its own armed forces. In The fallout of disintegration was arguably the most significant of any non-Russian republic as most of the USSR’s military industrial complex was in this republic along with 750,000 troops. When the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) were created, this ‘played a crucial role in ensuring the success of the state-building process in Ukraine’ (Jaworsky 1996: 223). Similar declarations were made by Moldovans in 1990 and Georgians in 1991 followed by Armenia, Azerbaijan and Lithuania (Foweks 1996: 169). By the end of 1990, many of the Soviet draft boards (the physical premises of these locations), were no longer operative and did not even have electricity or running water (Solnick 1999: 207). An important dynamic to consider here is that it became incredibly difficult and unrealistic for Moscow to be able to punish draft evaders in the republics, and even domestically, officials that sought to prosecute evaders faced difficult barriers (Solnick 1999: 207). The process of territorial disintegration led to new boundaries of governance being established through declarations and legal decrees that literally ended up shifting the flow of members of armed forces away from the USSR Military Defense to each republic. Breakaway territories also arose such as the Chechen Republic – here Dzhokhar Dudayev led an independence struggle which ended up in a prolonged set of conflicts and two Russian-Chechen wars that spanned most of the 1990s. In Lithuania, political elites called for reconstituting a national military with combined units that were independent of the USSR. A decree was issued that enabled civilians to serve on Lithuanian territory. A similar decree was issued several months earlier in 1989 in Georgia.

In total, the four identified pathways of defection led to a great physical drop in the Soviet Army which can be summarised by the following numbers: in 1985 the Soviet Armed Forces numbered 5.3 million. Although Gorbachev did cut the total number of people in the armed forces by half a million in 1988, the total number kept shrinking and different types of defections played a role in contributing to this decrease. By 1990 there were only 3.99 million, and by the time the Soviet Union morphed into the Russian Federation in late 1991, only 2.72 million remained. As noted by Brusster and Jones (1995), already in the fall of 1990, ‘the high command’s concern had deepened to alarm. Military leaders were not just concerned over the impact of republic sovereignty on armed forces manpower. In their view, what was at stake in the struggle between the republics and the center was no less than the union itself and the unified army’ (Brusster & Jones 1995: 8). The greater majority of this astounding decrease was due to subordinates resisting and defecting from service through a process of ‘lower level disintegration’ (Beissinger 2002: 574). On 7 May 1992, the newly constituted Russian Federation established its own armed forces.

Conclusion

This study has carried out the first comprehensive analyses of defections that arose during the collapse of the Soviet Union. Prevalent research on defection has framed this phenomenon as being integral to different empirical processes including revolutions, coups, coup attempts and civil war. The context of the Soviet collapse has been under-researched and apart from the 1991 coup attempt, there is a systematic deficit in public and scholarly knowledge of defection during the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Through investigation of 15 different Soviet republics, the ethnic makeup of the armed forces, their experiences in dealing with multiple nationalist and territorial movements, as well as a coup attempt, this study has identified four pathways that led to defection. In total, 13 out of 15 republics experienced at least one form of defection. These outcomes arose due to a heterogeneous collection of factors. Defections arose due to soldiers’ lack of disagreement with orders of repression as well as the fallout of post-repression dynamics (in three republics). Defections additionally occurred due to a coup being waged (in one republic), and due to hazing which interacted with ethnic antagonisms (in 13 republics), as well as due to territorial disintegration where republics became self-governing institutions over the span of a short number of months (in 12 republics).

These results reveal that a mixture of different factors was relevant in spurring multiple processes of defection during the Soviet downfall 1988-1991. Conceptually, this lends support to the claim that defection is an equifinal phenomenon in its nature because multiple pathways and causal mechanisms can be observed to bring about this outcome. Along these lines, this study has identified that similar forms of defection (e.g. draft resistance by subordinates and conscripts) can be brought about by more than one pathway. For these reasons, scholars are recommended to broaden their scope of analysis of the outcome of defection – this phenomenon should not be studied as an isolated process attuned to protest-state interactions or contexts featuring only mobilisation. Finally, the results of this study can be easily triangulated into other analyses of defection or into data sets featuring this outcome. The two-tier specification – commanders and subordinates (as drawn from Albrecth & Ohl), can be useful for subsequent research on defection and civil-military relations during periods of political instability. Future research should continue to stringently compare different processes of defection and comparisons should be made across variant historical eras and cross-national settings.

***

Alexei Anisin, Ph.D., is the Dean of the School of International Relations and Diplomacy at the Anglo-American University in Prague, Czech Republic. The author of two monographs and over 20 scientifically indexed studies, Dr Anisin has carried out qualitative and quantitative inquiries on political instability, rare forms of violence, and homicide, and holds a deep interest in international politics and historical change.

References

Albrecht, H. & Ohl, D. (2016): Exit, Resistance, Loyalty: Military Behavior During Unrest in Authoritarian Regimes. Perspectives on Politics, 14(1), 38-52.

Alexiev, A. & Wimbush, E. (1988): Ethnic Minorities in the Red Army. Boulder: Westview Press.

Anisin, A. (2020). Unravelling the Complex Nature of Security Force Defection. Global Change, Peace & Security, 32(2), 135-155.

Anisin, A. & Ayan Musil, P. (2021): Resistance and Military Defection in Turkey. Mediterranean Politics. Online first, <https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2021.1904746>.

Arnett, R. L., & Fitzgerald, M. C. (1990): Restructuring the Armed Forces: The Current Soviet Debate. The Journal of Soviet Military Studies, 3(2), 193-220.

Barany, Z. (1993): Soldiers and Politics in Eastern Europe, 1945–90: The Case of Hungary. New York: Springer.

Barnes, A. (2014): Three in One: Unpacking the “Collapse” of the Soviet Union. Problems of Post-Communism, 61(5), 3-13.

Beissinger, M. R. (1993): Demise of an Empire-State: Identity, Legitimacy, and the Deconstruction of Soviet Politics. In: Young, C. (ed.): The Rising Tide of Cultural Pluralism. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 93–115.

Beissinger, M. R. (2002): Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beissinger, M. R. (2009): Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism. Contemporary European History, 18(3), 331-347.

Betz, D. (2004): Civil-military Relations in Russia and Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

Blauvelt, T. K. (2003): Military Mobilisation and National Identity in the Soviet Union. War & Society, 21(1), 41-62.

Brooks, R. (2017): Military Defection and the Arab Spring. Oxford Research Encyclopedia. February 2017, <accessed online: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.26>.

Brooks, R. A. (2019): Integrating the Civil–Military Relations Subfield. Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 379-398.

Brubaker, R. (1994): Nationhood and the National Question in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Eurasia: An Institutionalist Account. Theory and Society, 23(1), 47-78.

Brusstar, J. H. & Jones, E. (1995): The Russian Military’s Role in Politics. Washington, DC: Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University.

Central Intelligence Agency (1983): Director of Central Intelligence SUBJECT: NIE 11/12-83, Military Reliability of the Soviet Union’s Warsaw Pact Allies, <accessed online: https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/cia-rdp83m00914r002700060001-0>.

Chenoweth, E., & Lewis, O. A. (2013): Unpacking Nonviolent Campaigns: Introducing the NAVCO 2.0 Dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 50(3), 415-423.

Clark, S. L. (2019). Soviet Military Power in a Changing World. London: Routledge.

Cornell, S. (2005): Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus. London: Routledge.

Cortright, D. & Watts, M. (1991): Left Face: Soldier Unions and Resistance Movements in Modern Armies. (Vol. 107). Westport: Praeger.

Croissant, A., Kuehn, D. & Eschenauer, T. (2018): The “Dictator’s Endgame”: Explaining Military Behavior in Nonviolent Anti-Incumbent Mass Protests. Democracy and Security, 14(2), 174-199.

Degaut, M. (2019): Out of the Barracks: The Role of the Military in Democratic Revolutions. Armed Forces & Society, 45(1), 78-100.

Dallin, A. (1992): Causes of the Collapse of the USSR. Post-Soviet Affairs, 8(4), 279-302.

Daucé, F. & Sieca-Kozlowski, E. (2006): Dedovshchina in the Post-Soviet Military: Hazing of Russian Army Conscripts in a Comparative Perspective. Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society, 28. Stuttgart: ibidem Verlag.

Daugherty III, L. J. (1994): Ethnic Minorities in the Soviet Armed Forces: The Plight of Central Asians in a Russian-Dominated Military. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 7(2), 155-197.

Eaton, K. B. (2004): Daily Life in the Soviet Union. London: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Eichler, M. (2011): Militarizing Men: Gender, Conscription, and War in Post-soviet Russia. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Emizet, K. N., & Hesli, V. L. (1995): The Disposition to Secede: An Analysis of the Soviet Case. Comparative Political Studies, 27(4), 493-536.

Fowkes, B. (1996): The Disintegration of the Soviet Union: A Study in the Rise and Triumph of Nationalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Geddes, B., Wright, J. & Frantz, E. (2014): Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions: A New Data Set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(2), 313-331.

George, A. L. & Bennett, A. (2005): Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Goertz, G. (2017): Multimethod Research, Causal Mechanisms, and Case Studies: An Integrated Approach. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hosking, G. (1991): The Awakening of the Soviet Union. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hough, J. (1969): The Soviet Prefects: The Local Party Organs in Industrial Decision-Making. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Isaacs, R. & Polese, A. (2015): Between “Imagined” and “Real” Nation-Building: Identities and Nationhood in Post-Soviet Central Asia. Nationalities Papers, 43(3), 371-382.

Jaworsky, J. (1996): Ukraine’s Armed Forces and Military Policy. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 20, 223-247.

Johnson, P. L. (2017): Virtuous Shirking: Social Identity, Military Recruitment, and Unwillingness to Repress (Doctoral thesis). Davis: University of California Davis.

Kalin, I., Lounsbery, M. O., & Pearson, F. (2022): Major power politics and non-violent resistance movements. Conflict Management and Peace Science. Online first, <https://doi.org/10.1177/07388942211062495>.

Karklins, R. (1994): Explaining Regime Change in the Soviet Union. Europe-Asia Studies, 46(1), 29-45.

Kass, I. & Boli, F. C. (1990): The Soviet Military: Back to the Future?. The Journal of Soviet Military Studies, 3(3), 390-408.

Knight, A. (1990): The KGB: Police and Politics in the Soviet Union. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Kushen, R. (1991): Conflict in the Soviet Union: Black January in Azerbaidzhan. Vol. 1245. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Lee, T. (2005): Military Cohesion and Regime Maintenance: Explaining the Role of the Military in 1989 China and 1998 Indonesia. Armed Forces & Society, 32(1), 80-104.

Lehrke, J. (2013): The Transition to National Armies in the Former Soviet Republics, 1988-2005. London: Routledge.

Lepingwell, J. W. (1992): Soviet Civil-Military Relations and the August Coup. World Politics, 44(4), 539-572.

Makara, M. (2013): Coup-Proofing, Military Defection, and the Arab Spring. Democracy and Security, 9(4), 334-359.

McLauchlin, T. (2010): Loyalty Strategies and Military Defection in Rebellion. Comparative Politics, 42(3), 333-350.

Moroz, O. (2011): Who Destroyed the Union? Moscow: Capital Publishers.

Nepstad, S. E. (2013): Mutiny and Nonviolence in the Arab Spring: Exploring Military Defections and Loyalty in Egypt, Bahrain, and Syria. Journal of Peace Research, 50(3), 337-349.

Odom, W. (1998): The Collapse of the Soviet Military. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pilster, U. & Böhmelt, T. (2011): Coup-Proofing and Military Effectiveness in Interstate Wars, 1967–99. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 28(4), 331-350.

Raevsky, A. (1993): Development of the Russian National Security Policies: Military Reform. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 6(4), 529-561.

Reese, R. (2002): The Soviet Military Experience: A History of the Soviet Army, 1917-1991. London: Routledge.

Sakwa, R. (1990): Gorbachev and His Reforms 1985-1990. Hertfordshire: Philip Allan.

Scott, H. F. & Scott, W. F. (1979) The Armed Forces of the USSR. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Seely, R. (2012): The Russian-Chechen Conflict 1800-2000: A Deadly Embrace. London: Routledge.

Sever, A. (2008): Istoria KGB [A History of KGB]. Moscow: Algorithm Press.

Sharp, G. (2005): Waging Nonviolent Struggle, 20th Century Practice and 21st Century Potential. Boston: Extending Horizons Books.

Simpson, M. & Hawkins, T. (2018): Primacy of Regime Survival. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, K. (2002): Mythmaking in the New Russia: Politics and Memory During the Yeltsin Era. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Solnick, S. L. (1998): Stealing the State: Control and Collapse in Soviet Institutions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Spivak, A. L. & Pridemore, W. A. (2004): Conscription and Reform in the Russian Army. Problems of Post-Communism, 51(6), 33-43.

Taylor, B. (2003): Politics and the Russian Army: Civil-Military Relations, 1689-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sultanov, C. (2004): Poslednii Udar Imperii [The Last Strike to the Empire]. Baku: Nafta Press.

Vallance, B. J. (1994): Corruption and Reform in the Soviet Military. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 7(4), 703-724.

Zhirokhov, M. (2012): Semena Raspada: Voyna i Konflikti na Territoriyi Byvshego SSSR [Seeds of Dissolution: War and Conflict on the Territory of the Former USSR]. St. Petersburg: BXV Press.