Abstract

This article implies that cinematic narratives project practical geopolitical discourses by using the example of Marvel Cinematic Universe’s success – The Avengers film franchise. The conceptualisation of imaginary threats in the films that follow the main storyline of the Avengers assembly, determined by the time and the geographic space, give those threats a symbolical manifestation that tends to overlap with the practical geopolitical notions of American foreign policy, as well as contemporary international politics. The interpretative textual analysis of the films’ narratives and their relations to world politics, hence, presents the central methodology of this article. The relation between those two has a capacity to transmit a subconscious message to blockbusters’ consumers about preferable practical geopolitical visions in contemporary world politics. Simply, the paper shows how cinematic narratives form an identity that is deeply securitised and able to capture the Zeitgeist of world’s politics.

Keywords

Introduction

Scholars of critical geopolitics focus their attention on the way in which ideas about places are constructed. By doing so, they are able to establish patterns that help to explain how those ideas shape political behaviour and how agendas are set, as well as how those ideas affect the everyday lives of ordinary people. Governments, supranational organisations, transnational corporations, various non-governmental organisations and every person has certain opinions, a clear or imagined picture of the geopolitical notions that surround us. Most of us have never been to Syria, but almost all of us have a certain perception about what that country currently looks like. Moreover, if you are an American who, e.g., has trouble locating Croatia, certain discourses – former Yugoslav state, EU and NATO member state, Game of Thrones – create certain mental maps that help to approximately place this country within a bigger, European context. The methodology of mental mapping is just one of many tools that critical geopolitics explore in its search to deconstruct the existing geopolitical discourses.

O´ Tuathail and Agnew define discourses as ‘sets of socio-cultural resources used by people in the construction of meaning about their world and their activities’[i]. Along the lines of poststructuralist thought, Martin Muller upgrades their definition by stating that geopolitical discourse is ‘always more than text, reflecting contextual, supra-subjective structures of meaning that are not exclusively expressed by textual means’[ii]. Geopolitical discourses are usually created largely under the strong influence of mediums – sometimes those mediums are political leaders, creators of foreign policies, statespersons or military authorities, other times they can be the mass media or various products of the popular culture. The first one can be defined as the practical geopolitical discourses, whilst the second are popular ones. The borders between these discourses are often blurred and they tend to overlap each other. Using interpretative textual analysis of the films’ narratives and their relations to world politics as a methodological tool, the paper focuses on the latter – to present the general understandings of popular geopolitics and the way in which practical geopolitical discourses appear in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s success The Avengers.

Blockbuster films pose themselves as a crucial part of popular culture. Even though there are bigger film industries, like Indian Bollywood, American Hollywood is, by far, the most famous in the world. Most films produced there are meant for audiences all around the world and Hollywood cinema has become a synonym for internationally successful films. Furthermore, in the last decade, one of the greatest impacts on this branch was made by the Marvel Cinematic Universe, whose films are in the top ten highest-grossing films in history. Accordingly, this research is focused on their most successful sequels of blockbuster films where the storyline of The Avengers develops – Captain America: The First Avenger, The Avengers, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Captain America: Civil War, Avengers: Infinity War, and Avengers: Endgame[iii]. Hence, the simple question this paper seeks to answer is – which geopolitical discourses appear in Marvel’s The Avengers’ blockbusters? By answering this simple question, the paper shows how the Zeitgeist of international politics is well captured in what Klaus Dodds calls ‘national security cinema’[iv]. Furthermore, it tells us in which way practical geopolitical discourses appear in cinematic narratives and how their appearance forms an identity that is deeply securitised and able to subconsciously send a message to blockbusters’ consumers about preferable practical geopolitical visions in contemporary world politics.

Popular Geopolitics in the Hollywood Cinematography

The world of international politics constantly transforms. Different entrants, factors and conditions at different times on different geographical terrains shape a constellation of relations that are hugely under the strong influence based on power. Power poses itself as a dominant virtue in molding political relations that are sufficient for dominance over specific geographical terrains. Once the terrain, in combination with political relations and built on power creates a political entity, most likely a state, it gets the label of territory. Thus, geopolitics studies politics on the certain geographic space defined as territory. Having the territory in the centre of its analysis, geopolitics develops various tools to approach different phenomena on it. At its early stages, geopolitics was misused as a tool of great powers – before and between world wars – to establish theories of their ideological understandings of territorial expansions. Those theories of classical (imperial) geopolitics were later deconstructed by the instruments of critical geopolitics.

The general idea behind critical geopolitics is that ‘intellectuals of statecraft construct ideas about places, these ideas influence and reinforce their political behaviors and policy choices, and these ideas affect how we, the people, process our own notions of places and politics’[v]. O’ Tuathail and Agnew give the theoretical framework for the analysis in critical geopolitics by defining it as a ‘discursive practice by which intellectuals of statecraft “spatialize” international politics and represent it as a “world” characterized by particular types of places, peoples and dramas’[vi]. This is the general premise that gives us a starting position in learning how to approach certain phenomena in the focus of geopolitical research. The interpretative and discourse analyses pose themselves as the central methodologies and, by doing so, allows the scientific approach to three different ways in which critical geopolitics is developed:

- formal geopolitics – ‘refers to the spatializing practices of strategic thinkers and public intellectuals who set themselves up as authorities on the totality of the world political map’[vii],

- practical geopolitics – ‘refers to the spatializing practices of practitioners of statecraft such as statespersons, politicians, and military commanders’[viii] and

- popular geopolitics.

In the words of Jason Dittmer, one of the defining notions of popular geopolitics has been its lack of a definition ‘not as a subject matter but as a group of people’[ix]. Dittmer here explains that many scholars in cultural studies, cultural geography and international relations are doing work that could be considered to be a part of popular geopolitics but do not use the term at all to refer to themselves or their work. Modern technology empowered by the globalisation of information, emphasises, even more, the outcomes of popular culture – both the real and the virtual spaces are filled with products of the mass media aiming to entertain the world’s population. The smartphone applications, e-books, magazines, video games, television, social networks, films, series and other means of popular entertainment completely overflow the world’s markets. Most of them, however, rely on different discourses that affect consumers’ ability to imagine and map the world. Hence, central to the development of critical geopolitics has been the ‘recognition of geopolitics as something ordinary that occurs outside of academic and policymaking discourse; this form of geopolitical discourse has been termed “popular geopolitics”’[x].

Joanna Szostek clarifies that popular geopolitics places itself in the subfield of human geography and is ‘concerned with peoples’ perceptions of different parts of the world and how those perceptions are (re)produced in popular culture’[xi]. Basically, the general assumption of popular geopolitics aims towards a simple goal – to detect and to describe how certain geographical representations of international politics are embedded and presented in the mass media. The visual and rhetorical imagery associated with the mass media has been discursively analysed by popular geopolitics’ scholars so that it became possible to discern how specific geographical understandings of regional and global politics were mobilised[xii]. Popular geopoliticians such as Klaus Dodds, Joanne P. Sharp, Jason Dittmer and Gearóid Ó Tuathail read popular mass media forms as texts, attempting to interrogate the political, social and cultural content of these representations of geopolitical space[xiii]. The central relationship in those attempts is the one between official geopolitics and the popular conceptualisations of that geopolitics – the mass media in the process of the creation of its products often reflect the official geopolitics provided by the state’s structures and elites.

Simon Dalby further develops the concept of the popular geopolitics emphasising the importance of cinema that, according to him, ‘provides an important space of confrontation and encounter for viewers and the recognition that the reception of filmic meaning is far from passive’[xiv]. Indeed, in the production of a good-quality film, often referred to in cinema as a blockbuster, territories and political spaces play a crucial role. This pose falls over as one of the most important case studies of critical geopolitics – Hollywood films give an imaginary perception of practical geopolitical notions in the world by framing them in simplified understandings of international politics. The representation of the world politics in Hollywood blockbusters is deeply rooted and intertwined with various geopolitical discourses that appear in the cinemas across the Globe and can be described as informal geopolitics – ‘largely silent and darkened space of the theatre provided an opportunity for conveying messages about the world, which few governments could resist, particularly during war and/or crises’[xv]. As Zorko and Mostarac suggest, informal geopolitics is perceived as the messenger that sends geopolitical messages to the ordinary people, in most cases without the direct influence of the political elites[xvi].

By being massively popular entertainment, the blockbusters manage to capture the wide attention of millions and millions of people across the Globe and their power lies ‘not only in its apparent ubiquity but also in the way in which it helps to create (often dramatically) understandings of particular events, national identities and relationships to others’[xvii]. The international community is moving to the cinemas in which acts of international politics, history or culture are re-conceptualised in the motion pictures that emit simplified understandings of those issues for the wide range of the audience. In other words, formal geopolitical discourses of world politics are being re-packaged into informal, fictional frames on the big screen.

Films and TV shows give people the ability to rely comfortably not only on the fact that good always wins, which is the most common outcome of these popular formats, but also to expand the scope of understanding of their national identities within much wider geopolitical narratives without even being aware of it.

The comics also played and still play a role in the re-conceptualisation of international politics – ‘awareness of the political potential of those texts for the distribution of favored messages among less literate populations has resulted in a wide variety of comics being produced either by the US government or by ideological allies of the US government for distribution in areas of Cold War conflict’[xviii]. Furthermore, the political relevance of Captain America’s comics after September 11 not only defines what America is, but it also firmly reminds the reader, tacitly assumed to be American, of his or her individual identity as an American and is told what that means in relation to the rest of the world[xix].

Together with the comics, as stated earlier, there are other products of the mass media that capture geopolitical discourses of spatialised reality. However, the attempts of geopolitics to examine ‘the ways in which actors and dramas are arranged on a world stage or a kind of “global chessboard” of political positions’, which makes films a ‘unique way of arranging these dramas and actors and of attempting a kind of specialization and visualization of boundaries and dangers and American identity’ is connected to ‘the geopolitical constructions and ideological codes of Hollywood films’[xx].

Films provide concrete solutions for geopolitical challenges by building moral geographical concepts able to distinguish us from them, good from bad, allies from adversaries. One could conclude that cinemas have an ideological function led by the direct hand of the political elites, but it requires broader research to prove such a hypothesis. Instead, my idea is to put focus on these films in order to try to understand outlines of practical geopolitical discourses captured by the film industry in their projects. By doing so, I contribute to the particular understandings of how and with what outcomes some places become a part of self-estimation, identity and relationships with other stakeholders of international politics, no matter which, positive or negative, contexts that relationship is built on. Moreover, the interpretative textual analysis of Marvel’s The Avengers narratives correspond with practical geopolitics, and hence, it subconsciously sends a message to blockbusters’ consumers about preferable geopolitical visions in contemporary world politics. In other words, the cinematic narratives influence the consumers’ self-identification with certain practical geopolitical phenomena of international politics’ Zeitgeist.

The way in which practical geopolitics of (American) foreign policy is staged in popular geopolitics of the Hollywood cinematography starts to be clearer once one takes into consideration the concept of, what Dodds calls, ‘national security cinema’[xxi]. This concept presents highly imaginative threats that the USA faces: The Soviets and communists in general, the Nazis, terrorists, extraterrestrials, meteors, uncontrollable natural forces and machines. These threats are simple tools of Hollywood filmmakers and represent different geopolitical discourses of the factual American foreign policy. The conceptualisation of the imaginary threats in films, determined by time and geographical space, gives those threats a symbolic manifestation – the discourse – that tends to overlap with practical geopolitics. The ability to read those discourses, interpret them and even compare them to others is a general premise of popular geopolitics.

The post-September-11 paradigm in practical geopolitics completely changed across the world, especially in the United States. Perceiving terrorism and new security threats like cyberterrorism, human trafficking, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, radicalism, regional threats, etc., became the central focus of security and defense strategies. Soon enough, this practical geopolitics’ paradigm was applied to popular geopolitics of Hollywood cinematography. Behind Enemy Lines from 2001, The Bourne Ultimatum from 2007, War of the Worlds from 2005, The Iron Man from 2008, The Dark Knight from 2008 and others provide opportunities for people to watch, to get entertained, but also to reflect on contemporary international politics[xxii]. Even more, some of those blockbusters, more successfully than others, breathe the life of comics into these characters creating live-action cinematographic sequels capable of capturing the geopolitical Zeitgeist of international politics.

Without a doubt, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, an ‘American media franchise and shared universe that is centered on a series of superhero films, independently produced by Marvel Studios and based on characters that appear in American comic books published by Marvel Comics’[xxiii], is the most successful in its field of business with more than $22.5 billion total income from the world box offices[xxiv]. The series of superhero films are divided into four phases and this paper focuses on the films published so far where the storyline of Marvel’s The Avengers develops[xxv] – Captain America: The First Avenger (2011)[xxvi], The Avengers (2012)[xxvii], Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015)[xxviii], Captain America: Civil War (2016)[xxix], Avengers: Infinity War (2018)[xxx], and Avengers: End Game (2019)[xxxi].

The Avengers is a group of superheroes with different supernatural abilities that fight imaginary threats to the USA and the world. The six films mentioned earlier engage deeply in the constellation of international relations based on power, influence and practical geopolitics. Case studies were selected based on three assumptions: the great impact of The Avengers on the world, the profit these films make, the fans and the targeted audience. The first film of the Avengers from 2012, simply titled The Avengers, is according to Box Office Mojo eight the highest-grossing film in history with more than $1.5 billion profit[xxxii]. Its sequel, Avengers: Age of Ultron from 2015 takes eleventh place with a profit of more than $1.4 billion, Infinity War is fifth with more than $2 billion, whilst the last sequel –End Game – breathes down Avatar’s neck as the second in the history of all-time box office worldwide grosses[xxxiii].

Besides having one of the most profitable and notable film characters in the world, Marvel’s The Avengers have numerous fans and followers around the Globe. Finally, the targeted audience is not just limited to the young population and children. Some of the most eminent names in Hollywood cinema like Samuel. L. Jackson, Anthony Hopkins, Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Downing Jr., as well as the multilevel approach towards the complexity of the struggles and threats in films, often attract 40+ audiences. Taking all these variables into account, one can understand the importance of researching outlines of formal geopolitical discourses in those films. Hence, the central interest of this paper is to seek an answer to a simple question – which geopolitical discourses appear in Marvel’s The Avengers blockbusters?

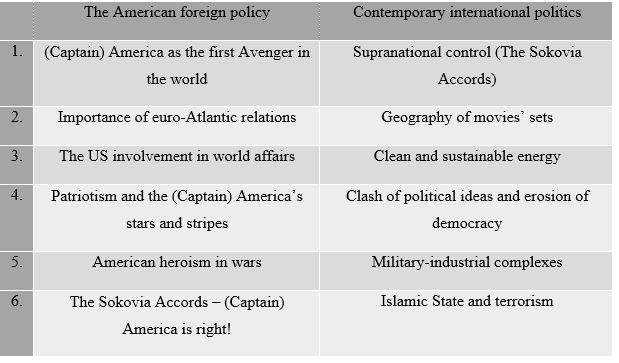

This article approaches the interpretative textual analysis of geopolitical notions in The Avengers’ storyline by introducing two levels of the practical geopolitical discourses coded into two factors: the American foreign policy and the contemporary international politics. Methodologically, I interpret geopolitical discourses that appear in the films, clarify fictional foundations based on which the films are created and seek to connect them with the lived reality in both the American foreign policy and the contemporary international politics. In the final stage of this research, the elaboration is coded into twelve different geopolitical discourses, six for each factor. Finally, an adequate interpretation and the conclusion are offered at the end of this article.

Understanding Fictional through Factual Discourses in The Avengers Storyline

American Foreign Policy

The first film in this research is Captain America: The First Avenger[xxxiv]. The Marvel Cinematic Universe gave special attention to this Avenger, presenting him as the leader of the team. This is something that audiences learn in Avengers: The Age of Ultron film when Tony Stark clearly states that he was the one paying for everything, but that Captain America was the boss[xxxv]. A great impact that the Marvel comics, especially the ones about Captain America, had in World War II[xxxvi] [xxxvii] [xxxviii], is now revised and revisited in the blockbuster Captain America: The First Avenger by presenting, within the Marvel Universe, Steve Rogers as the patriotic super-soldier, dressed in American colours and fighting the Nazis. Symbolising the USA, Captain America in this film reminds the audience of the crucial role that the USA played in the war against the Nazis. Moreover, the whole plot shows the importance of American interference in European affairs. After this engagement, in geopolitical terms, the USA never left this continent. The central part of the film’s plot illustrates the strong Transatlantic/Euro-Atlantic bond. Captain America symbolises not just the heroism of American war veterans engaged in War World II, but also of the whole state that selflessly helps those who stand with the Americans. Even the act of sacrifice Captain America did in the end by crashing the plane on the no man’s land of the Artic[xxxix], shows how America always sacrifices itself for the sake of its allies.

An era of absolute world supremacy of one power, the USA, starts immediately after World War II[xl]. With small ups and downs, it is kept until today. However, after waking up from a 70-year coma, Captain quickly learns about the time and the things he missed. One of them is when an agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. (an espionage and anti-terrorist agency) informs him about the little modifications to his uniform and Captain surprisingly asks: ‘Aren't the stars and stripes a little...old fashioned?’ and gets the answer: ‘Everything that's happening, the things that are about to come to light, people might just need a little old fashioned’[xli]. These surprises indicate how seriously America was agitated after September 11, and this reminder stresses the importance of values that the stars and stripes represent and that they will never go out of fashion as long as America stands.

In World War II, Captain America only needed minor help from normal soldiers to fight evil, but this time he needs an assembly of superheroes, equal to him, to stand together for a set of desirable or shared values. The supremacy and triumphalism the USA had after the collapse of the Nazi Reich, and later the Soviet Union, slowly vanishes after September 11. Contemporary threats are hybrid, the uprise of the Russian Federation and other BRIC countries shadows US supremacy, and the world’s order shifts from unipolarity to multipolarity of international relations[xlii]. Suddenly, the USA should rely on allies to fight contemporary security challenges. Not just one superhero, but a team of them, the Avengers, are required to fight (imaginary) threats.

The way this geopolitical constellation is mapped throughout the films can be noticed by paying attention to the geographical location of sets. The locations breach the traditional borders of Western Europe as the only trustworthy ally and move the sets further east to Central and Eastern Europe, South Korea and Africa. The imaginary Republic of Sokovia in Eastern Europe vividly illustrates the American geopolitical perspective on the sources of contemporary threats. First, locating something in the East relates to orientalism, contrary to the West and western values[xliii] [xliv]. Second, the discourse of Eastern Europe is used to illustrate the traditional place of hostility due to factual Cold War discourse. Third, the terrorists they deal with are agents of HYDRA, a secret organisation created during World War II. Eastern Europe (the communists) and HYDRA (the Nazis) represent and/or symbolise traditional American enemies that the audience recognises from the comics, but in the films, they are re-branded in such a way that they are given a certain geographical illusion of easternisms[xlv] and political violence that cherishes hybrid warfare methods. In this portrayal, it is notable how the USA's practical geopolitical focus shifts from the Central and Eastern Europe, further east, towards the Middle East where the Republic of Sokovia can symbolise Syria, and HYDRA represents terrorist organisations like the Islamic State’s fighters. This is discussed further within contemporary international politics.

Another important narrative that appears in the films, especially in the original The Avengers film from 2012, Avengers: Infinity War from 2018 and Avengers: Endgame from 2019, is the geopolitical imagination of New York as the unofficial capital of the world[xlvi]. In the films, the extraterrestrial attacks happen in New York City – first by the Asgardian Loki who opens a breach above the City[xlvii], then by Thanos’ servants who land in Downtown Manhattan searching for the Time Stone, one of the six Infinity Stones[xlviii], and, finally, in the last sequel that reflects on previously mentioned events due to time travel[xlix]. Moreover, the Avengers Headquarters is in the downtown of this city, and there's the fact that some of the most important Avengers are born and raised in the city (for example, Spiderman is from Queens, Captain America from Brooklyn and Iron Man is from long Island). The geopolitical imagination of New York as the world’s unofficial capital is deeply rooted in the ability of the American cultural diplomacy that branded the city through the export of their cultural product, and also in the fact that the world’s most important organisation, the United Nations, is located there.

On one hand, as the story develops further, the character of Captain America progressively weakens. On the other hand, the Avengers present an assembly of the most superior individuals in the world. These two factors intertwine from the first time the Avengers were introduced[l], all the way to when they directly clash causing the division between former teammates in Captain America: Civil War[li]. The tensions between the members of the ‘world’s antiterrorist coalition’ led by (Captain) America, reach its peak soon after someone – like the United Nations in the film – questions the supremacy of judgment of the leader, one man or country. The Sokovia Accords, proposed as the political measure of the United Nations to control the superheroes’ war on terror, weakened Captain America and left him only with the most faithful allies. Captain America, while attending a funeral of his close friend, Agent Carter, at one point in Civil War is advised by Carter’s granddaughter: ‘When the mob and the press and the whole world tell you to move, your job is to plant yourself like a tree beside the river of truth, and tell the whole world – No, you move’[lii]. How far (Captain) America is willing to go, is illustrated by his readiness to engage in a war against former teammates. However, in Infinity War[liii] and Endgame[liv], he is ready to team back up with his former allies in order to save the world from a greater threat, Thanos.

Contemporary International Politics

Discourses such as the USA's world supremacy and the question of the legitimacy of the United Nations, fall into the practical geopolitical discourses of international politics. The direct confrontation of world nations, represented by the UN, with the exceptional individuals, the Avengers, who seem to intervene in all parts of the world without a legitimate international mandate to do so, resembles actual incapacity of the highest international body to keep the strongest countries in line and prevent them from intervening in the internal affairs of other, weaker, countries. The source of that incapacity is the lack of legitimacy.

Captain America: Civil War has two main characters in this confrontation with completely different views on the Sokovia Accords[lv]. On one side there is Captain America with his followers who represent free-market capitalism and patriotism, while on the other, Iron Man with his team feel guilty for the damage the Avengers, and he personally, have caused around the world, representing in this way perverted global techno-determinism. The two fractions among the assemble engage in an open fight. The patriotic team of Captain America refuses to yield under the pressure of the UN, while their former teammates gather around Iron Man and pose themselves as guardians of the international order that favours the neoliberal paradigm of international relations. In practical geopolitical understanding, the civil war between the Avengers presents the clash of political ideas – the contemporary political situation in the world - that now more than ever questions if democracy and all its values are universal[lvi]. Based on the same notions, Team Captain America questions the legitimacy of Iron Man’s team to pose themselves as defenders of international order. This clash of political ideas on the international community transmits to nation-states – while on the international level the clash happens because of the ‘right’ of stakeholders to act in a certain way, on the national level the clash is between liberal and illiberal democracy.

Furthermore, Iron Man himself presents military-industrial complexes, one of the most profitable industries in the world. Upgraded due to serious threats that threatened the USA and the world after September 11, the military-industrial complexes expanded their capacities with one simple goal: to achieve perfection in the further development of military technology[lvii] [lviii] [lix]. The same pattern follows the character of Iron Man in films – as the CEO of Stark Industries, the world’s leading company for military technology, Tony Stark, aka Iron Man, pushes very hard the idea of further development of military technology. Hiding under the veil of neoliberalism, Tony Stark becomes a technofascist. However, when he accidentally develops Ultron, an AI interface that turns against the Avengers, it takes over the Internet and decides to exterminate the human race from the planet. Then Stark feels guilty for all the bad the Avengers did while saving the world from Ultron[lx]. This is the main reason he yielded in front of the UN and the Sokovia Accords – not because of his beliefs, but because of the guilt and worries that he has about his profit.

Related to the previous discourses, another storyline occurs – Tony Stark and the Avengers search for the Tesseract, ‘a crystalline cube-shaped containment vessel for the Space Stone, one of the six Infinity Stones that predate the universe and possess unlimited energy’[lxi]. The Tesseract is mentioned in all of the films in this research – it appears in 1942 when Johann Schmidt, the head of the HYDRA, a secret Third Reich organisation, uses it to defeat the Allies in World War II. Eventually stopped by Captain America and his unit, the Tesseract is lost in the Arctic ice with the Captain himself[lxii]. After recovering it from the sea, Stark Industries try to use its enormous energy for further military development and as a device that can create clean and sustainable energy. However, Thor’s brother Loki from the planet Asgard, breaches through and uses its energy to open a wormhole above New York City for the extraterrestrial attack on the Earth[lxiii]. Later, Tony Stark uses it to create the AI, Ultron, which, as mentioned before, takes over the Internet and turns against the Avengers[lxiv].

The Tesseract and other Infinity Stones in practical geopolitical terms of international politics represent the search of humanity for technology that can produce clean and sustainable energy, while these battles between the Avengers and different adversaries in the films reflect another discourse – the global war on terror. Throughout all the films, it is more than clear who the good guys and who the terrorists who want to conquer the world or dominate it are. To achieve that, all bad guys, no matter if they are the members of HYDRA, eastern mobs or extraterrestrials, use hybrid warfare methods similar to those used by contemporary terrorists: confiscation of modern technological achievements from the Avengers and the Stark Industries, cyber-attacks, terrorist bombings, espionage, sabotage and infiltration. Old Marvel’s enemies from the Cold War comics still stay a big part of contemporary Marvel films, with a slight change – methods they nowadays use greatly resemble the ones used by the Middle-Eastern terrorist fractions, e.g. the Islamic State or Al-Qaida.

Within these two factors, the article offers 12 different narratives altogether from the films, six for each factor, that are interpreted and compared with the practical geopolitical discourses of the American foreign policy and international politics. As seen in Table 1, each of those narratives is coded and placed within the two factors. In order to establish a better understanding of popular geopolitics and outlines of practical geopolitical discourses in Marvel’s The Avengers, Table 1 offers the codification of narratives that appear in the films and its practical geopolitical understandings. Bearing in mind the complexity of struggles in both, the reality of practical geopolitics and the films, this table brings only the outlines of potential interpretations regarding the application of contemporary geopolitical challenges to Marvel’s Avengers.

Table 1.: The codification of geopolitical narratives in Marvel’s Avengers films

The first factor frames the most notable narratives of chosen films that reflect the practical geopolitical discourses of the American foreign policy, while the second one does the same, only relating to contemporary international politics. The fact that all these films are made in Hollywood and they were a big international success explains why there are geopolitical narratives not only on the national level but also on the international. All coded narratives in this table represent a combination, or better yet, an integration, of practical geopolitical discourses in the films’ discourses.

Conclusions

The codification of twelve different geopolitical discourses that appear in films where the central role is the plot about Marvel’s The Avengers assembly indicates a very important conclusion – not only do they appear in the films, but they all come under the common denominator of what Klaus Dodds defines as ‘national security cinema’[lxv]. This notion narrows the two factors, the American foreign policy and the contemporary international politics, used in this research, into one frame. Within this, it is possible to conclude that even though both factors differ regarding the geopolitics of scale within which they study geopolitical discourses, they still stay deeply rooted in the American perspective on both geopolitical levels. The first level, the American foreign policy factor, focuses more on the national level of analysis, whilst the second one, the contemporary international politics, goes out of the national borders and deals with the practical discourses that appear in the international arena. The common ground, however, remains deeply Americanised in the case of both of the factors.

The central goal of this research has been achieved – to show outlines of practical geopolitical discourses captured by the cinematic narratives in The Avengers film series, to code them into two different factors and to frame them back in Dodds notion of the national security cinema. The research contributes to the understanding of how and with what outcomes some places and events in the films can become a part of the geopolitical self-estimation and identity, as well as the awareness of the US geopolitical relationships with other stakeholders of international relations. The threats that appear in the films are simple tools of the Hollywood filmmakers and represent different geopolitical discourses of the factual American foreign policy and contemporary international politics. The conceptualisation of the imaginary threats in the films, determined by the timeframe, limited understandings of practical geopolitics and geographical space, give those threats a symbolic manifestation capable of capturing the geopolitical Zeitgeist of the Americanised view on both the American foreign policy and contemporary international politics.

Bearing in mind the complexity of threats that occur all around the world, different mechanisms American administrations apply to tackle them, as well as constant and unpredictable changes in the globalised world, one could conclude that cinemas have an ideological function led by the direct hand of political elites. Cultural diplomacy, political warfare, fake news and/or propaganda are all mechanisms that can tackle complex threats in front of the American administrations, create a better image for the global and for the domestic audiences, reshape interpretations of practical geopolitical discourses or deal with contemporary challenges.

Nevertheless, the interpretative textual analysis of Marvel’s The Avengers narratives showed that, in examined cases, they not only correspond with practical geopolitics, but also have an ability to subconsciously send a message to blockbusters’ consumers. By answering the central research question, I was able to show that capturing national and international politics’ Zeitgeist in films enables a transmission of preferable geopolitical visions and forms an identity that is deeply securitised. The securitised identity represents an unaware self-identification of the blockbusters’ consumers with practical geopolitics and lived realities, and it is built in their national identities through the lenses of often dramatical cinematic narratives. Hence, the interpretation of these narratives in Marvel’s The Avengers film franchise showed that what Dodds calls national security cinema has a capacity to capture and transmit subconscious messages about preferable practical geopolitical visions in contemporary world politics.

In the end, the intention of this research was to establish a clearer picture of intertwining cinematic narratives of The Avengers films with practical geopolitical discourses. Questions like how this intertwining happens, if it’s orchestrated by the government, if the Hollywood cinematography is used as a tool of political warfare; etc., are all questions for future research in this field. This article, hence, contributes to similar research in the field by implying that cinematic narratives in Hollywood are, as The Avengers case study shows, often a reflection of lived geopolitical realities and they have a capacity to influence subconsciously or even to shape and reshape national identity of millions of their consumers worldwide.

Nikola Novak is affiliated with the Centre for International Studies at the ISCTE – University Institute of Lisbon, Portugal, and may be reached at nikola_novak@iscte-iul.pt.

Endnotes

[i] O’Tuathail, Geraoid and Agnew, John (1992) Geopolitics and Discourse: Practical geopolitical reasoning in American foreign policy. Political Geography, Vol 11. No. 2. pp. 190 - 204

[ii] Muller, M. (2008) Reconsidering the concept of discourse for the field of critical geopolitics: Towards discourse as language and practice. Political Geography 27, pp. 322 – 338

[iii] fandom.com (2021a) Marvel Cinematic Universe https://marvelcinematicuniverse.fandom.com/wiki/Marvel_Cinematic_Universe (Accessed 29/04/2021)

[iv] Dodds, Klaus (2007) Geopolitics: A very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press

[v] Fouberg, Erin H., Alexander B. Murphy and H. J. de Blij (2009) Human Geography: People, Place, and Culture (9th ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons

[vi] O’ Tuathail and Agnew 1992, p. 192

[vii] O’Tauthail, Geraoid (2005) Critical Geopolitics. Taylor & Francis e-Library, p. 46

[viii] O’ Tuathail 2005, p. 46

[ix] Dittmer, Jason (2010) Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, p. xviii

[x] Dittmer, Jason and Nicholas Gray (2010) Popular Geopolitics 2.0: Towards New Methodologies of the Everyday. Geography Compass 4/11, pp. 1664 – 1677

[xi] Szostek, Joanna (2017) Popular Geopolitics in Russia and Post-Soviet Eastern Europe, Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 69 no.2, pp. 195 – 201

[xii] Dittmer, Jason and Klaus Dodds (2008) Popular Geopolitics Past and Future: Fandom, Identities and Audiences, Geopolitics, vol. 13 no. 3, pp. 437 – 457

[xiii] Saunders, Robert A. (2012) Undead Spaces: Fear, Globalisation, and the Popular Geopolitics of Zombiism, Geopolitics, vol. 17 no.1, pp. 80 – 104

[xiv] Dalby, Simon (2008) Warrior geopolitics: Gladiator, Black Hawk Down and The Kingdom of Heaven. Political Geography 27 pp. 439 – 455

[xv] Dodds, Klaus (2006) Popular geopolitics and audience dispositions: James Bond and the Internet Movie Database (IMDb). Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Vol 31/2 pp. 116 – 130

[xvi] Zorko, Marta and Hrvoje Mostarac (2014) Popularna geopolitika Japana: geopolitički diskursi anime serijala. Media Studies. 5 (10) pp. 4 – 18

[xvii] Dodds, Klaus (2008) Hollywood and the Popular Geopolitics of the War on Terror. Third World Quarterly, 29:8, pp. 1621 – 1637

[xviii] Dittmer, Jason (2007) The Tyranny of the Serial: Popular Geopolitics, the Nation, and Comic Book Discourse. Antipode. 39/2, pp. 247 – 268

[xix] Dittmer, Jason (2005) Captain America's Empire: Reflections on Identity, Popular Culture, and Post-9/11 Geopolitics. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 95:3, pp. 626 – 643

[xx] Power, Marcus and Andrew Crampton (2005) Reel Geopolitics: Cinematographing Political Space. Geopolitics. 10:2, pp. 193 – 203

[xxi] Dodds 2007, p. 151

[xxii] Dodds, 2008, p. 1621

[xxiii] Wikipedia.org (2019) Marvel Cinematic Universe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marvel_Cinematic_Universe. (Accessed 23/03/2019)

[xxiv] The-numbers.com (2021) Box Office History for Marvel Cinematic Universe Movies https://www.the-numbers.com/movies/franchise/Marvel-Cinematic-Universe#tab=summary (Accessed 28/04/2021)

[xxv] fandom.com 2021a

[xxvi] Feige, Kevin (producer) and Joe Johnston (director). (2011) Captain America: The First Avenger [Motion picture]. United States: Marvel Studios

[xxvii] Feige, Kevin (producer) and Josh Whedon (director). (2012) The Avengers. [Motion picture] United States: Marvel Studios

[xxviii] Feige, Kevin (producer) and Josh Whedon (director). (2015) Avengers: Age of Ultron. [Motion picture] United States: Marvel Studios

[xxix] Feige, Kevin (producer), Anthony Russo (director) and Joe Russo (director). (2016) Captain America: Civil War [Motion picture]. United States: Marvel Studios

[xxx] Feige, Kevin (producer), Anthony Russo (director) and Joe Russo (director). (2018) Avengers: Infinity War. [Motion picture] United States: Marvel Studios

[xxxi] Feige, Kevin (producer), Anthony Russo (director) and Joe Russo (director). (2019) Avengers: End Game. [Motion picture] United States: Marvel Studios

[xxxii] Boxofficemojo.com (2021) Top Lifetime Grosses – Worldwide https://www.boxofficemojo.com/chart/ww_top_lifetime_gross/?area=XWW (Accessed 28/04/2021)

[xxxiii] Boxofficemojo.com (2021)

[xxxiv] Feige and Johnston, 2011

[xxxv] Feige and Whedon, 2015

[xxxvi] Dittmer, Jason (2013) Captain America and the nationalist superhero: metaphors, narratives, and geopolitics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, pp. 64, 81, 106

[xxxvii] Fellman, Paul (2009) Iron Man: America's Cold War Champion and Charm against the Communist Menace. Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 1, No 2, pp. 11 – 22

[xxxviii] Genter, Rober (2007) ‘‘With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility’’: Cold War Culture and the Birth of Marvel Comics. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 953 – 978

[xxxix] Feige and Johnston, 2011

[xl] Aggarwal, Mamta (2019) How USA Became the Only Super Power of the World? http://www.historydiscussion.net/world-history/how-usa-became-the-only-super-power-of-the-world/850 (Accessed 17/04/2019)

[xli] Feige and Whedon, 2012

[xlii] Ambrosio, Thomas (2017) Challenging America's Global Preeminence: Russia's Quest for Multipolarity. New York: Routledge

[xliii] Hall, Stuart (2006) The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power. In: Roger Maaka and Chris Andersen (ed.) The Indigenous Experience: Global Perspectives. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press pp. 165 – 173

[xliv] Melegh, Attila (2006) On the East-west Slope: Globalization, Nationalism, Racism and Discourses on Eastern Europe. Budapest: CEU Press

[xlv] Ballinger, Pamela (2017) Whatever Happened to Eastern Europe? Revisiting Europe’s Eastern Peripheries. East European Politics and Societies and Cultures. Vol. 31 No 1. pp. 44 – 67

[xlvi] Sherman, Eugene J. (2019) New York - Capital of the Modern World http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/forward.htm (Accessed 24/04/2019)

[xlvii] Feige and Whedon 2012

[xlviii] Feige, Russo and Russo 2018

[xlix] Feige, Russo and Russo 2019

[l] Feige and Whedon, 2012

[li] Feige, Russo and Russo, 2016

[lii] Feige, Russo and Russo, 2016

[liii] Feige, Russo and Russo, 2018

[liv] Feige, Russo and Russo, 2019

[lv] Feige, Russo and Russo, 2016

[lvi] Crouch, Collin (2000) Coping with Post-Democracy. London: Fabian Society

[lvii] Byrne, Edmund F. (2017) Military Industrial Complex https://philarchive.org/archive/BYRMC-2 (Accessed 2/05/2019)

[lviii] Hinshaw, John and Peter N. Stearns (2014) Industrialization in the Modern World: From the Industrial Revolution to the Internet vol. 1 A – P. Santa Barbara: ABC – CLIO, pp. 316-317

[lix] Der Derian, James (2009) Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment-Network. Taylor & Francis e-Library

[lx] Feige and Whedon 2015

[lxi] fandom.com (2021b) Tesseract. https://marvelcinematicuniverse.fandom.com/wiki/Tesseract (Accessed 24/4/2021)

[lxii] Feige and Johnston 2011

[lxiii] Feige and Whedon, 2012

[lxiv] Feige and Whedon, 2015

[lxv] Dodds 2007, p. 151