Abstract

The independent role of international institutions has been taken to be the core of the debate between institutionalists and realists. This study explores the EU’s relations with Russia in two cases as a testbed for this debate. Institutional independence, meaning restriction on the ambitions of powerful states on the one hand, and the impact of less powerful states on decisions on the other, are taken here to be the opposite of the power politics of realism. Two cases are studied to show how the EU safeguards the rights and interests of small members and restrains the ambitions of powerful ones to make the case for the institutionalists’ argument. The article also shows how a supranational entity like the European Commission is relatively more successful than an intergovernmental one like the Council of Europe in furthering institutionalisation, even in high-profile cases which are lynchpins of the EU’s Russia policy. This is in line with institutionalists’ argument about the significance of institutionalisation, as the European Commission, through its regulatory mechanism, sets overarching rules and links issues, brings transparency by forcing information sharing, dispels the fear of cheating and paves the ground for more comparative empirical research to evaluate the depth of institutionalisation in supranational and intergovernmental institutions.

Keywords

Introduction

To have a role in world politics, the European Union (EU) must be able to align its member states (MS) with a common decision-making procedure. This applies to various areas but is more critical in foreign policy as it has been universally regarded as a national affair. In particular, EU-Russia relations is even more critical since it is ‘the most divisive factor in EU external relations policy’ (Schmidt-Felzmann 2008: 170).

In maintaining alignment, institutionalism regards institutions as potentially capable of acting independently, while many realists see them as nothing more than a mirror of the balance of power. This debate between neo-realism and institutionalism needs to be addressed empirically (Waever & Neumann 1997: 22). The EU, and, in particular, its foreign policy decision-making, can be regarded as a good case to study. On the other hand, as in institutionalism and the studies on integration in Europe, intergovernmentalism and supranationalism are two major mechanisms discussed as having some taming effect on the power of individual member states, we need to see which one is more effective in practice. Thus this article attempts to answer two questions: 1) In two cases of the EU’s relations with Russia, i.e. Lithuania’s dispute over the PCA and the rift over Nord Stream, were the decisions taken by the EU independent of power distribution inside the Union? 2) What were the differences between supranationalism and intergovernmentalism inside the EU regarding the depth of institutionalisation and hence constraining the effects of individual states’ power on its decisions?

To cite the EU as an example of institutions’ being independent of power politics, Maria Viceré explored the role the EU’s high representative played in consolidating a common position of recognising Kosovo’s independence among the EU members. Member states’ national interests were so divergent that it would not have produced that outcome was it not for the EU’s institutional capacity (Viceré 2016). Basically, the fact that between 1993 and 2008 the EU took more than 1,000 common decisions reveals the independent role of the EU in world politics because common positions could hardly be reached by power politics and consonance is rare in world politics (Thomas 2009: 341). As another example, Lisa Martin took the Falkland Crisis as an example and held that it was for the EEC that a country like Greece imposed sanctions on Argentina sooner than the US. Normally, one would expect the US to have stepped in first as it had much stronger ties with the UK than a country like Greece (Martin 1992: 153).

In these studies, the independent role of institutions is uncovered in cases where the results are different from the expectations rising from power politics. One of the manifestations of power politics is that ‘the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must’ (Thucydides et al. 2009: liii). So, institutions can assert their independence when they protect the weak and restrict the strong. In that sense, one needs to find cases where small and powerful members have divergent views on the EU’s foreign policy. Cases like Russia’s sanctions after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 are not revealing as they pit powerful members like Italy against other powerful members like Britain.

Additionally, to have more convincing and more generalisable results, one should investigate extreme cases where conflict of interest happens between the smallest and the most powerful members. Moreover, to compare supranationalism with intergovernmentalism, one needs cases where different types of organs inside the EU are involved. Also, those cases must be old enough so that they would have disclosed their final results. Following these measures, we have chosen Lithuania’s veto in 2007 to test intergovernmentalism and the dispute over Nord Stream to test supranationalism.

In what follows, we first lay the theoretical foundation and define ‘institutionalisation’ by scrutinising Robert Keohane and John Mearsheimer’s debate on the role of institutions in world politics. Second, process tracing as the research method is shortly discussed. In the third section, Lithuania’s veto in the Council of the European Union and the subsequent negotiations are traced, so that we can draw the timeline and discover the process that the Council went through to settle the dispute. In the fourth part, the same process is traced to the dispute over the Nord Stream project. Finally, the findings of the two cases will be compared to draw a comparison and conclusion.

Institutions: autonomous actors or mirroring power relations?

In search of the role that the EU plays in world politics, one group believes that power politics is the independent variable and institutions are just a mediating factor. For example, Julian Clark and Alun Jones discussed how ‘political elites mediate Europeanization through their EU decision-making and decision-taking’ (Clark & Jones 2011). Or, Jonas Tallberg underlines that institutional and individual capacities are just a mediator for the ‘structural power asymmetries’ inside the EU (Tallberg 2008). As another example, Anke Schmidt-Felzmann said that as long as EU members’ interests have not been homogenised, they will not stop giving priority to their bilateral relations with outside countries like Russia and institutions cannot change the situation (Schmidt-Felzmann 2008).

Another group believes that institutions can have an independent role for various reasons. For example, from a normative point of view, Andreas Warntjen discussed how much ‘norm-guided behaviour’, compared to the rational choice models, plays a role in the EU decision-making procedure (Warntjen 2010). Or, from a rational point of view, Kenneth Abbott and Duncan Snidal argued that centralisation is one of the system characteristics that brings independence to an institution (Abbot & Snidal 1998).

This difference constitutes the core of the debate between realism and institutionalism. While rationality and utilitarianism are the fundamental assumptions for both realism and institutionalism (Keohane & Martin 1995: 39), they hold different views on the role of institutions. Mearsheimer contends that institutions are only a reflection of power distribution and do not have an independent impact on states’ behaviour. They are only mediating variables (Mearsheimer 1994/95: 13). He argues that empirical evidence can support institutionalism only if it shows that cooperation could not have happened without a given institution (Mearsheimer 1994/95: 24).

The viewpoint that trusts individual entities to supply public goods comes from the classical economy. Adam Smith, in his famous book ‘The Wealth of Nations’, claimed that ‘an order is spontaneously formed from the self-interested acts and interactions of individual units’ (Waltz 1979: 89). This idea lays the foundation of neo-realism and its reliance on the balance of power as an ordering mechanism. It dismisses Wilsonian idealism and mechanisms of collective security (Waltz 1979: 203).

Robert Keohane, on the other hand, maintains that institutions are important because they facilitate cooperation by mechanisms like issue linkage and information sharing and dispel the fear of cheating (Keohane & Martin 1995). Since Waltz considered realism as analogous to the free market economy (Waltz 1979: 91), one can consider idealism as analogous to the planned economy, and liberal institutionalism as analogous to the Keynesian economy. Introducing the low-level equilibrium trap, Keynes showed that market equilibrium might not be reached by just an invisible hand (Miller 2008: 75). Institutions are necessary to remedy market failures. By the same token, there can be times when cooperation in international relations cannot be ensured, even though all players are cooperative. In such circumstances, institutions are necessary to remedy the failure of power politics and stabilise the system.

Table 1: Political Economy versus Theories of International Relations

|

Political Economy |

|

||

|

Free Market Economy |

Keynesian Economy |

Planned Economy |

|

|

International Relations |

|||

|

Realism |

Liberal Institutionalism |

Idealism |

|

Source: Authors

As the Keynesian Economy does not intend to overthrow the free market system but only to remedy its failures, liberal institutionalism in IR does not intend to overthrow power politics but to remedy its failures. In fact, liberal institutionalism transcends the dichotomy between realism and idealism. Moreover, Keohane did not claim that institutions matter in every single case and under any circumstances, but the burden is on the shoulders of social sciences to show where and when international institutions are important (Keohane & Martin 1995: 40–42). This article will show that the EU succeeded in acting against the imperatives of the balance of power.

Since issues in IR are mainly multifaceted, the methodological problem is how one can separate the outcome of the balance of power from those of institutions. Keohane admitted that it is not easy to find an ideal quasi-experimental condition to test the independent role of institutions (Keohane & Martin 1995: 47). One solution he suggested was to look for times when changes in underlying conditions, i.e. the balance of power, do not coincide with the evolution of institutions. Institutions usually lag behind their surrounding conditions. Different factors, like uncertainty, transaction costs or institutional barriers to change may account for this inertia (Pollack 1996: 438). In such circumstances, the role of institutions can be disentangled from power relations. But for the EU, since its institutions constantly change by negotiating new treaties, these institutional barriers are relatively low, compared to, for example, the United Nations Security Council which has not changed for nearly 80 years. So, one cannot just wait for those moments to come.

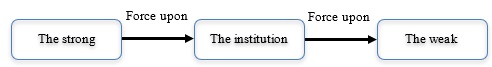

In the case of the Falkland crisis, Lisa Martin maintained that if power politics dominated the relations, the US would have stepped in sooner than some EEC members like Greece. By this method, she separated the role of institutions from the results of power politics. She compared the outcome of a given institution with what should be expected from power politics (Martin 1992: 153). This is how we measure institutionalisation too. In power politics, as Figure 1 suggests, one expects that a powerful player must be able to force its interest upon the weak player, and institutions like the EU are only a transmission belt to transmit that force.

Figure 1: Expectations from power politics

Source: Authors

In this study, institutionalisation is defined as a dynamism that works in the opposite direction in which the weak can force their aim upon the strong through institutions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Expectations from institutionalism

Source: Authors

Research method

To find the processes through which institutions reverse power politics (i.e. supranationalism and intergovernmentalism), process tracing is employed. It is mainly used for the analysis of interactions rather than structures (Checkel 2008: 116). So, it is useful for studying negotiations inside the EU institutions. In process tracing, the timeline of important decisions and events will be drawn up to the moment when the dependent variable appears. Here, it is the time when the failure or the success of institutionalism becomes evident. Thus, theoretical expectations determine the beginning and the end of the timeline (Ricks & Liu 2018: 843).

The type of process tracing here is theory-testing (Beach & Pedersen 2013: 146) as it tests the theory of liberal institutionalism introduced by Keohane, and the independent variable is a binary that has two values: intergovernmentalism and supranationalism. The dependent variable is institutionalism based on the definition provided before. Since there is no official guideline for conducting a process tracing and the method is flexible in different situations, these steps, suggested by Ricks and Liu will be followed:

- identify hypotheses,

- establish timelines,

- construct a causal graph, that connects independent variable to the dependent variable,

- identify alternative choice or event,

- identify counterfactual outcomes,

- find evidence to invalidate counterfactual outcomes (Ricks & Liu 2018: 842–845).

The hypothesis here is the independent role of the EU. So it is assumed that the Council could have secured Lithuania’s position and the Commission could have restricted Germany’s ambitions. The timeline must include the negotiations in both the Commission and the Council to reveal the precise mechanism that brings success or failure. The causal graphs will be built on those mechanisms. To invalidate counterfactual outcomes that could have been produced by alternatives, one needs to investigate similar cases, just like Lisa Martin (1992) compared the outcome of the ECC in the Falkland Crisis with the delayed reaction of the US.

Lithuania’s veto in the Council of the European Union

The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) was first signed in 1997 between the EU and Russia, and in ten years, was the legal basis of their relations, covering a whole range of issues from trade to energy (Delegation of the European Union to Russia 2016). As it was to come to an end in December 2007, the Council of the European Union (the Council) needed a mandate from the European Commission (the Commission) to start negotiations for a new agreement (Gardner 2014). The PCA was used to build a unified front in relations with Russia (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2008) and played a crucial role in the EU integration in CFSP.

In November 2005, Russia imposed sanctions on Poland’s agricultural products, mainly meat, claiming that they fell short of the required standards (Euractiv 2007). In response, Poland, alongside Lithuania vetoed the mandate for PCA negotiations with Russia (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2008).[1] In November 2007, when liberals in Poland took power, the tune changed toward Russia (World Bulletin 2008) and as a result, Russia lifted its ban (Euractiv 2007). Poland too lifted its ban on the Commission’s mandate (Gardner 2014). This timeline indicates that the reason behind Russia’s change of mind was not Poland’s veto in the Council. It was the change in the underlying circumstances and the EU institutions had no impact on it.

When Poland lifted its veto, Lithuania became the sole vetoer. It demanded Russia’s cooperation for three legal cases: cooperation in investigating the Medininkai Massacre in 1990 (Pavilionis 2008: 176), cooperation in investigating the incident of deploying tanks to Lithuania in 1991 which killed 14 people and injured another 700 (Deutsche Welle 2008b), and finally cooperation in investigating the disappearance of a Lithuanian businessman in Kaliningrad in 2007 (Times of Malta 2008). Lithuania also had two more demands: first, it looked for an end to energy security threats from Russia[2] and wanted to include Georgia and Moldavia’s security concerns in negotiations.[3] The demand for Georgia was highly timely because a few months later Russia invaded Georgia. With this background information, the process tracing develops through the aforementioned steps.

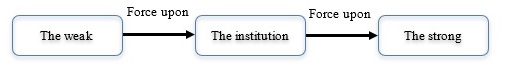

a) Hypothesis 1: intergovernmentalism, through mechanisms such as organisational inertia and normative entrapment, decreases the effect of power politics.

b) Timeline: Process tracing starts from the moment Lithuania announced in the Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) that it would veto the mandate for the talks with Russia until its demands had been entered into the negotiations. From then, Lithuania came under pressure from other members in order to lift the veto. The Estonian foreign ministry claimed that they had the same concerns but it was better to continue talks with Russia (Deutsche Welle 2008a). He complained that Lithuania was putting the whole block in an unbearable situation (Euractiv 2008). Spain’s secretary of state for European affairs also said that there were many potential interests in negotiations with Russia and there would be long discussions ahead. So negotiations would be better to start as quickly as possible. Its British counterpart also said that the EU must start cooperation and partnership talks with Russia and that the Union’s unity was of great importance (Deutsche Welle 2008a).

On the other side, the Slovenian foreign minister, whose country held the presidency of the Council, expressed that it was necessary to ensure Lithuanians that they could rely on the EU’s cooperation (Gardner 2014). Therefore, on 24 April 2008, Slovenia prepared a proposal for a compromise that included Lithuania’s demands. Slovenia’s foreign ministry asked for further consultation with Lithuanian officials. Despite the fact that the meeting of foreign ministers in Luxemburg on 29 July was the last chance to reach an agreement, Lithuania made it clear that the Commission’s mandate must be put off the table during the meeting until the final agreement on a compromise would be reached. Its foreign minister expressed his country’s willingness for discussing energy security and judicial cooperation with Russia. He contended that if the UK inserted the Litvinenko[4] case in the mandate, why did they think Lithuania should not seek justice in the same manner (Times of Malta 2008)?

Despite Slovenian efforts, Lithuania did not lift its veto and the foreign ministers did not reach a deal. This caused a great commotion and frustration, especially for Slovenia which wanted the PCA to be signed during its own presidency. Other members also wanted the PCA to be signed before their first meeting with the new Russian president, Dimitrov Medvedev, as a symbol of a new start in their relations. But Lithuania’s foreign minister said that the quality of the deal was more important than its schedule (Euractiv 2008). However, informal talks between Vilnius and Brussels continued (Euractiv 2008) and unexpectedly, the dispute was solved in a meeting between the foreign ministers of Poland, Sweden, Slovenia and Lithuania in Vilnius in which they agreed to put Lithuania’s demands on the EU’s written negotiating position, and in turn, Lithuania consented to lift its veto on the commission’s mandate (Gardner 2014). Therefore, in the COREPER meeting on 21 May 2008 and in the Council’s meeting five days later, the mandate was passed unanimously (Pavilionis 2008: 175).

c) Causal graph: Based on the abovementioned timeline, Figure 3 represents the causal chain.

Figure 3: Construct a causal graph for Lithuania Challenging the Council

Source: Authors

d) Alternative choices: Lithuania was forced to give its consent.

e) Counterfactual outcomes: The written position did not fulfil Lithuania’s expectations and Lithuania did not believe in other members’ arguments when it lifted its veto.

f) Evidence that invalidates counterfactual outcomes: In the EU’s written negotiating position, it is said that ‘the list of [the] demands would receive due attention in the course of the EU-Russia talks’. But the demands were written in a separate declaration, in order not to hinder the negotiations. Also, they were written in general terms, so that they could be ignored more easily (Lobjakas 2008). Therefore, it seems it was not forceful enough.

Moreover, a few months later, Russia invaded Georgia in support of separatists in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. While on 16 August, France had mediated a peace deal between them, on 26 August President Medvedev announced that Russia recognised the independence of both regions (Nichol 2009: 9). Poland and Lithuania once again tried to use their veto power to stop negotiations with Russia, but this time the EU overrode their veto. On 9 November, Poland and Lithuania admitted that they did not have the power to halt negotiation while it was underway and the Commission did not need another mandate when a mandate had already been given. On 14 November, the EU-Russia summit was held in France, but a Lithuanian representative told Reuters that Lithuania did not agree with these negotiations (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2008).

The fact that a few months later Lithuania raised its objection again reveals that Lithuania had not been content and did not agree with the argument put forward by other MSs when it lifted its veto. Also, the fact that Poland had gained nothing after two years of persisting on its demands (see above) and, in addition, the PCA had been automatically extended, showed Lithuania that it could not gain anything except some pangs of sympathy from Eastern European friends (Rettman 2006). Thus these pieces of evidence could not invalidate the counterfactual outcomes of the alternative choices and as a result, the first hypothesis is rejected which means intergovernmentalism, in this case, could not actualise institutionalism. So, this empirical study could not disprove the Realistic point of view that says institutions are just a mirror of power distribution.

Nord Stream: East versus West

Nord Stream was one of the most disputable energy transition projects in Europe (Vaughan 2019). Countries in Eastern Europe were highly dependent on Russia’s oil and gas, while Russia depended on them to transit gas to its customers in Western Europe. After the commissioning of this project, Russia would not need their land for the transition and this mutual interdependency would grow into a unilateral dependency on behalf of Russia. This was the main reason that these countries disagreed with the project. For the first line, the EU had not expressed opposition at first, saying that it benefited Europe by increasing the volume of gas importation to the EU (Szul 2011: 59). For the second line, the Commission’s first assessment was that it was only related to countries located alongside the line, but after some objections, Brussels had to rethink its position (Keating 2017).

This assessment was contradictory to their assessment of the South Stream as they announced that the South Stream pipeline was against the EU laws and must be stopped. South Stream could have possibly made Italy the energy hub in the Mediterranean. But by the construction of this new line, the whole of Western Europe would become dependent on the German route (Maio 2019).

With the rising tension between Russia and Europe in the aftermath of the Ukrainian crisis in 2014, a growing number of countries started to voice their concerns about Nord Stream. Ukraine’s transit income was equal to its whole defence budget (Brzozowski 2018). So, by the weaponisation of gas export, Russia was able to strip Ukraine of its defence money. On the other side of the dispute was Germany, a powerful member of the EU whose clout was even enhanced after the Ukrainian crisis. Germany was not significant in terms of its military power or natural resources (Siddi 2018a: 4). Its military budget ranked third among MSs in 2014 (Perlo-Freeman et al. 2015: 2). However, its economy was stronger than other members, and since the military solutions for the Ukrainian crisis had been opted out from the beginning, Germany’s military rank barely hurt its hegemonic influence (Siddi 2018a: 2). Table 2 displays Germany’s superior economy at that time, compared to the most powerful EU members in 2019.

Table 2: GDP ranking among the five biggest economies of the EU

|

Country |

GDP Nominal 2019 (in million US$) |

|

Germany |

3,845,630 |

|

United Kingdom |

2,827,110 |

|

France |

2,715,520 |

|

Italy |

2,001,240 |

|

Spain |

1,394,120 |

Source: World Bank

Germany also carried considerable clout in the EU institutions. It had 96 seats in the EU Parliament before Brexit, well above France’s 74 and the UK’s 73 seats (European Parliament 2020). Additionally, Germany was the biggest contributor to the EU budget (see Table 3) and this also indicated its institutional strength.

Table 3: Contribution of member states to the EU budget

|

Country |

Net Contribution to the EU Budget 2018 (in million Euro) |

|

Germany |

17,213 |

|

United Kingdom |

9,770 |

|

France |

7,442 |

|

Italy |

6,695 |

|

The Netherlands |

4,877 |

Source: European Commission

To liberalise the EU energy market, the so-called Gazprom clause in the third energy package (approved in 2009 and came into force in March 2011) introduced some restrictions on ownership and gave discretion to the member states to decide whether a given case was a security threat or not (Goldthau & Sitter 2014: 1464). Moreover, to separate ownership and operation, the ‘unbundling’ clause forced the pipeline owners to let other gas providers use their pipelines. The goal was to prevent the creation of a monopoly by the owners (Szul 2011: 63). But it may have doubted the economic feasibility of projects (EuropeanCEO 2019). This law restricted Gazprom’s opportunities for investment in Europe’s energy market (Maio 2016: 3).

With this background information, the process tracing develops through the following steps.

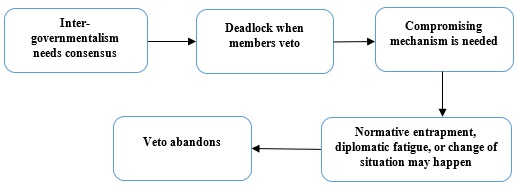

a) Hypotheses: the second hypothesis is that supranationalism can uphold institutionalism.

b) Timeline: in 2012, the Commission suspected that Gazprom breached EU laws on competition. So it started an investigation into Gazprom activities (Siddi 2018b: 1565). In 2015, the Commission raised its objection to Gazprom based on three anti-competitive practices: first, the destination clause in Gazprom’s contracts with European countries prevented them from re-exporting purchased gas to other countries; second, price discrimination which helped Russia pursue its ‘divide and rule’ policy; and third, Russia forced Poland and Bulgaria to participate in the South Stream project and to give up control of their investment in Yamal–Europe pipeline, otherwise they would be cut off from the gas supply (Siddi 2018b: 1565). At first, Russia disdained the Commission’s regulations, but when the Commission threatened to fine Gazprom 10 percent of its yearly income, they had no choice but to take it seriously and they started negotiations with the Commission (Siddi 2018b: 1565–1566).

In September 2015, a few months after a group of Western European companies signed an agreement with Gazprom to develop the Nord Stream project, ten Eastern European countries sent a letter to the Commission and complained about Western European countries’ negligence over other MSs’ interests. They asked the Commission to discuss the problem at the EU level (Deutsche Welle 2015). In 2017, the Commission passed a new law to make the third energy package applicable to the European parts of the pipelines (European Commission 2017). Germany tried to block the decision by the rule of blocking minority in the Council (Euronews 2019). To that end, it needed a number of countries that amounted to 35 percent of the EU population. Member states from Nordic, Baltic and Eastern Europe did not follow suit, and Italy and Spain did not support Germany (Euronews 2019), probably for their resentment over the cancellation of the South Stream. This made France’s cooperation very important because France was an old ally that had the third-largest population in the Union (Worldometers 2019). Without France, Germany had only votes from the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Bulgaria and Hungry (all countries that benefited from the project), which altogether held only 27 percent of the population in the block (Bershidsky 2019).

At first, France, like Spain and Italy, decided to stay neutral. But later, on 5 February 2019, it expressed that the Commission directive must be implemented (Johnson 2019). This was a huge blow to Germany (Irish & Rinke 2019). Heretofore Germany could disregard criticism, but after France’s turnabout, it was no longer possible (Shelton 2019). Surprisingly, three days later, the two countries came to a compromise in which Germany accepted the Commission’s directive, and instead, it would reserve the right of oversight of the directive.[5] However, Germany’s oversight was not completely arbitrary. First, its oversight should not have been detrimental to competition in the EU, and second, whenever it led to disagreement between Germany and the Commission, the Commission would overrule (European Parliament 2019). Before that, the oversight was at the EU’s discretion, and France had supported that idea (France 24 News Agency 2019). On 6 February, one day after France stopped Germany from building a blocking minority, the two countries made a compromise on the EU copyright reform. It is said that France probably used this issue as a bargaining chip to extract concessions on some other issues in the EU, like the common Eurozone budget and debt system (Keating 2019).

Finally, on 12 February, representatives of the Commission, the Parliament and member states signed a deal based on the Germany-France compromise. On 4 April, the EU Parliament approved the deal to become law (Pressroom 2019). Then it was published in the EU’s Official Journal and entered into force 20 days later. Member states had nine months to incorporate it into their national law (EU Parliament 2019). This law keeps the flow of gas through Ukraine unchanged (Vaughan 2019). Thus Gazprom filed a lawsuit against the EU executive body at the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in October 2019 (Istrate 2019) and Russia brought the issue to the World Trade Organisation (Shelton 2019). Germany first claimed that the issue was not related to the EU, and that national governments must decide on it (Keating 2019), but later, its chancellor, Angela Merkel, said that Nord Stream should not leave Ukraine ‘in the lurch’ (Johnson 2018).

Like the case of Falkland, it is worth exploring the US reactions to the Nord Stream dispute and comparing it with other players (Martin 1992). Both Barack Obama and Donald Trump spoke against Nord Stream, although in the Trump administration, the opposition gained stronger momentum. In Stockholm on 25 August 2016, then Vice President Joe Biden asserted that Nord Stream was a bad deal (Reuters 2016). One official in Obama’s administration also claimed that the Nord Stream just like Brexit weakens Europe (Crisp 2016). Germany and its ambassador in Washington resented such statements and exclaimed that the Nord Stream was a European matter which must be decided by Europeans (Gurzu & Schatz 2016). This rhetoric grew bitter in the Trump era. On 17 May, Trump announced that ending Nord Stream 2 was one of the conditions to make a trade deal with Europe. The heaviest criticism, however, was expressed in the meeting with NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg on 11 July 2018, in which Donald Trump called Germany ‘captive to Russia’ (Gotev 2018). The pressure gradually increased to higher levels such as threatening to impose sanctions. On 12 July 2019, Trump, in a meeting with Poland’s president in the White House, threatened to impose sanctions on the Nord Stream (Holland & Gardner 2018). That threat became reality on 1 August 2009 when the US imposed sanctions on the European companies involved in the Nord Stream 2 project (Aljazeera 2019).

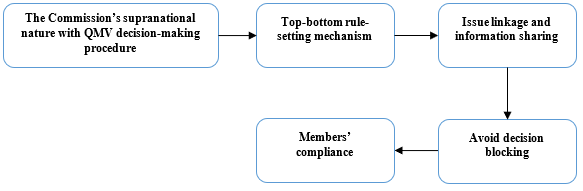

c) Causal graph: Figure 4 is the causal graph based on the above-mentioned timeline.

Figure 4: Construct a causal graph for the Commission Challenging Germany (step 3)

Source: Authors

d) Alternative choices:

- Germany might be a benign hegemon who willingly preferred the security concerns of Eastern Europe to its own interests.

- The directive was not so important for Germany’s energy security.

- It was France who managed to stop Germany through its bilateral relations and a favourable balance of power.

e) Alternative counterfactual outcomes:

- Germany’s resistance was not serious.

- The directive would not pose any significant threat to Germany’s energy security.

- Any other powerful country, no matter inside or outside the EU, could have produced the same result.

f) Evidence that invalidates counterfactual outcomes:

- Germany seriously engaged in considerable efforts to undo the Commission’s decision by building a blocking minority in the Council. It leaves no doubt that Germany single-mindedly was against the directive. So, the first counterfactual outcome can be invalidated by the evidence provided before.

- The prolongation of the construction of the pipeline and the delay in project commissioning, caused by the Commission’s legislation put the gas supply to houses and industries in Germany in danger. The project was set to be finished by the end of 2019, the year that the contract between Ukraine and Russia was going to terminate. With Germany’s submission to the Commission’s decision, this deadline expired. Moreover, Russia’s complaints indicate that the directive had serious effects on the benefits that the pipeline had for Germany’s partner, and in turn for Germany itself. Therefore, the second counterfactual outcome cannot be supported by empirical evidence.

- Long before France’s mediation, the US, which is by far more powerful, had tried to stop Germany. The result that France produced was because of its institutional position and voting power inside the EU institutions, not because of its national power. The regulatory power of the Commission, which made it capable of setting rules and regulations, enabled France to play its hand. Otherwise, France could not have achieved such a result in just three days, and even if it could, it would be humiliating for Germany to be stopped by another nation-state.

To sum up, all pieces of evidence that have been collected in the timeline, rejected alternative choices and their outcomes, and therefore, the second hypothesis cannot be rejected. This means that this case study disproves the realists’ point of view that institutions are ‘always’ a mirror of power distribution.

Conclusion

This study sought to answer the question of how the European Union can act independently of power politics by restricting the ambitions of powerful members and defending the rights and interests of smaller states. The result showed that in the EU’s decision-making procedure, the EU Commission, by its supranational quality and therefore, with its regulatory power, was more successful in overcoming power politics, while intergovernmentalism of the Council did not prove to be independent of power politics. As was shown, the regulatory mechanism of supranationalism makes issue linkage and information sharing possible and prevents humiliating enforcement by one member upon another one. But the compromising mechanism in intergovernmentalism creates unbearable normative entrapment that frustrates small members.

Additionally, the empirical results disproved the idea that international institutions are just a mirror of power politics. This does not mean that institutions always matter, but it just gives a counterexample of what Realists claim is always true. The study has other implications too. First, institutions matter even in cases where relative gains matter, not just in cases where fear of cheating matters. In the Commission’s directive on the Nord Stream, fear of cheating was not the main concern, otherwise, MSs would not accept Germany’s oversight. Second, institutions work on security domains too. Although Germany believed that the Nord Stream ‘is a purely economic initiative’ (Rettman 2018), most MSs could not help but consider the project as a security concern. Offshore pipelines are twice as expensive as onshore ones (Przybyło 2019: 9). So, this project is justifiable mainly in terms of its security benefits for Russia. Therefore, institutions matter even in security issues. Third, the study showed that the role of institutions in the security domain is to provide information, as Keohane maintained. In the case of Nord Stream, when Germany implements the directive, other members will find out how Germany interprets the directive. That is why they accepted the directive to resolve the dispute.

To conclude, one can safely say that supranationalism is more reliable for smaller members of the Union than their veto power in intergovernmental arrangements. In the same manner, powerful members must take supranationalism more seriously than intergovernmental negotiations. The important mechanism that produces such an outcome is the regulatory power that comes with supranationalism. Normative entrapment may seem to have an effect here too. It is a situation in which an actor accedes to a less preferred position or plays along just because they don’t want to be seen as the black sheep of the family (Munyi 2013: 228). Although normative entrapment could have happened in both cases and perhaps both Germany and Lithuania were likely trapped, in Lithuania’s case, the Council was not able to whitewash the sheep.

***

Homeira Moshirzadeh is a professor at the Department of International Relations, University of Tehran. Her main scholarly interests are IR theory, theories of social movements, and Iran’s foreign policy. She has published many books and articles in Persian on theories of international relations and foreign policy, social movements, and Feminism. She has translated some of the major IR texts into Persian, including Hans Morgenthau’s Politics among Nations and Alexander Wendt’s Social Theory of International Politics. Some of her articles have been published in English in Security Dialogue, International Political Sociology, All Azimuth, and the Iranian Journal of International Affairs. Her articles on IR theories, IR in Iran, dialogue of civilisations, cultural studies, and women’s studies have appeared in edited volumes in Persian and English.

Issa Adeli is a researcher and policy advisor who received a master’s degree in International Relations from the University of Tehran and a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration. He is interested in global security and strategic studies including EU security affairs, US foreign policy in the Persian Gulf, great power competition in the Middle East, sanction policy, and defense policy.

References

Abbot, K. W. & Snidal, D. (1998): Why States Act through Formal International Organizations? The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32.

Aljazeera (2019): New US Sanctions Take Aim at Russia-Led Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. Aljazeera, 8 January, <accessed online: https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/sanctions-aim-russia-led-nord-stream-2-pipeline-190731181707578.html>.

Beach, D. & Pedersen, R. B. (2013): Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bershidsky, L. (2019): No, France and Germany Haven’t Fallen Out. Bloomberg, 8 February, <accessed online: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-02-08/france-germany-haven-t-fallen-out-over-nord-stream-2-pipeline>.

Brzozowski, A. (2018): Nord Stream 2 Exposed as Russian Weapon against NATO. Euractiv, 30 October, <accessed online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/nord-stream-2-exposed-as-russian-weapon-against-nato>.

Checkel, J. T. (2008): Process Tracing. In: Klotz A. & Prakash D. (eds.): Qualitative Methods in International Relations. A Pluralist Guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 114–127.

Clark, J. & Jones, A. (2011): Telling Stories about Politics: Europeanization and the EU's Council Working Groups. Journal of Common Market Studies, 49(2), 341–366.

Carafano, J. J. (2021): Nord Stream 2: No Strategic Gains for the United States. Geopolitical Intelligence Services AG, 25 August, <accessed online: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/nord-stream-biden>.

Crisp, J. (2016): Senior Obama Official: Nord Stream 2 and Brexit May Weaken EU Energy Security. Euractiv, 31 March, <accessed online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/interview/senior-obama-official-nord-stream-2-and-brexit-may-weaken-eu-energy-security>.

Delegation of the European Union to Russia (2016): Legal Framework. The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement. The Delegation of the European Union to Russia, 13 July, <accessed online: http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/delegations/russia/eu_russia/political_relations/legal_framework/index_en.htm>.

Deutsche Welle (2008a): EU Deadlocked over Negotiations with Russia. DW News, 30 April, <accessed online: https://p.dw.com/p/Dqsi>.

Deutsche Welle (2008b): Lithuania Cuts Deal to Lift Veto on EU-Russia Talks. DW News, 5 December, <accessed online: https://www.dw.com/en/lithuania-cuts-deal-to-lift-veto-on-eu-russia-talks/a-3330889>.

Deutsche Welle (2015): Eastern EU Countries Complain about Pipeline Deal. DW News, 11 November, <accessed online: https://www.dw.com/en/eastern-eu-countries-complain-about-pipeline-deal/a-18879865>.

Deutsche Welle (2019): EU Adopts French, German Compromise on Nord Stream 2 Pipeline to Russia. DW News, 8 February, <accessed online: https://p.dw.com/p/3D0V1>.

EU Parliament (2019): Natural Gas: Parliament Extends EU Rules to Pipelines from Non-EU Countries. News EU Parliament, 4 April, <accessed online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20190402IPR34673/natural-gas-parliament-extends-eu-rules-to-pipelines-from-non-eu-countries>.

Euractiv (2007): Russia Lifts Embargo on Polish Meat. Euractiv, 21 December, <accessed online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/med-south/news/russia-lifts-embargo-on-polish-meat>.

Euractiv (2008): EU Presidency Upset over Lithuanian Veto of EU-Russia Accord. Euractiv, 30 April, <accessed online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/news/eu-presidency-upset-over-lithuanian-veto-of-eu-russia-accord/823658>.

European Commission (2017): Energy Union: Commission Takes Steps to Extend Common EU Gas Rules to Import Pipelines. The European Commission, 8 November, <accessed online: https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-4401_en.htm>.

European Parliament (2019): EU Gas Market: New Rules Agreed Will Also Cover Gas Pipelines Entering the EU. The European Parliament, 13 February, <accessed online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20190212IPR25908/eu-gas-market-new-rules-agreed-will-also-cover-gas-pipelines-entering-the-eu>.

European Parliament (2020): Infographic: How Many Seats Does Each Country Get in the European Parliament? The European Parliament, 31 January, <accessed online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/eu-affairs/20180126STO94114/infographic-how-many-seats-does-each-country-get-in-in-the-european-parliament>.

European CEO (2019): Relying on Russia – the EU’s Nord Stream 2 Dilemma. European CEO, 3 July, <accessed online: https://www.europeanceo.com/home/featured/relying-on-russia-the-eus-nord-stream-2-dilemma>.

Euronews (2019): France Key as Germany Fights EU Rules that Threaten Nord Stream 2. Euronews, 2 July, <accessed online: https://www.euronews.com/2019/02/07/france-key-as-germany-fights-eu-rules-that-threaten-nord-stream-2>.

France 24 (2019): France, Germany Compromise on Russia's Nord Stream II Gas Pipeline. France 24 News Agency, 8 February, <accessed online: https://www.france24.com/en/20190208-france-germany-compromise-russias-nord-stream-ii-gas-pipeline>.

Gardner, A. (2014): Lithuania Lifts Veto on EU-Russia Deal. Politico, 12 April, <accessed online: https://www.politico.eu/article/lithuania-lifts-veto-on-eu-russia-deal

Goldthau, A. & Sitter, N. (2014): A Liberal Actor in a Realist World? The Commission and the External Dimension of the Single Market for Energy. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(10), 1452–1472.

Gotev, G. (2018): Trump Begins NATO Summit with Nord Stream 2 Attack. Euractiv, 7 November, <accessed online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/trump-begins-nato-summit-with-nord-stream-2-attack>.

Gurzu, A. & Schatz, J. J. (2016): Great Northern Gas War. Politico, 17 February, <accessed online: https://www.politico.eu/article/the-great-northern-gas-war-nordstream-pipeline-gazprom-putin-ukraine-russia>.

Holland, S. & Gardner, T. (2018): Trump Considering Sanctions over Russia's Nord Stream 2 Natgas Pipeline. Reuters, 6 December, <accessed online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gazprom-nordstream-usa/trump-considering-sanctions-over-russias-nord-stream-2-natgas-pipeline-idUSKCN1TD267>.

Irish, J. & Rinke, A. (2019): In Blow to Germany, France to Back EU Rules on Nord Stream 2. Reuters, 2 July, <accessed online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-gazprom-nordstream/in-blow-to-germany-france-to-back-eu-rules-on-nord-stream-2-idUSKCN1PW1IN

Istrate, D. (2019): Angered by New Gas Transit Rules, Gazprom Sues EU. Emerging Europe, 10 August, <accessed online: https://emerging-europe.com/news/angered-by-new-gas-transit-rules-gazprom-sues-eu>.

Johnson, K. (2018): Is Germany Souring on Russia’s Nord Stream? Foreign Policy, 10 April, <accessed online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/04/10/is-germany-souring-on-nord-stream-ukraine-gazprom>.

Johnson, K. (2019): France and Germany Face Off over Russian Pipeline. Foreign Policy, 7 February, <accessed online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/07/france-and-germany-face-off-over-russian-pipeline-nord-stream-putin-macron-merkel>.

Keating, D. (2017): Washington Scores a Victory in Battle over North Sea Pipeline. Forbes, 9 November, <accessed online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davekeating/2017/11/09/washington-scores-a-victory-in-battle-over-north-sea-pipeline/#704be66821b1>.

Keating, D. (2019): Why Did France Just Save Nord Stream 2? Forbes, 8 February, <accessed online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davekeating/2019/02/08/why-did-france-just-save-nord-stream-2/#5c43bc756055>.

Keohane, R. O. & Martin, L. L. (1995): The Promise of Institutionalist Theory. International Security, 20(1), 39–51.

Lobjakas, A. (2008): EU: New 'Eastern' Division of Labor Lays Groundwork for Partnership Deal with Russia. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 25 May, <accessed online: https://www.rferl.org/a/1117544.html>.

Maio, G. d. (2016): A Tale of Two Countries: Italy, Germany, and Russian Gas. Brookings, 18 August, <accessed online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/fp_20160818_demaio_tale_of_two_countrie.pdf>.

Maio, G. d. (2019): Nord Stream 2: A Failed Test for EU Unity and Trans-Atlantic Coordination. Brookings, 22 April, <accessed online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/04/22/nord-stream-2-a-failed-test-for-eu-unity-and-trans-atlantic-coordination>.

Martin, L. L. (1992): Institutions and Cooperation: Sanctions during the Falkland Islands Conflict. International Security, 16(4), 143–178.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (1994/95): False Promise of International Institutions. International Security, 19(3), 5–49.

Miller, R. C. (2008): International Political Economy: Contrasting World Views. New York: Routledge.

Munyi, E. N. (2013): Getting to Yes: Belief Convergence and Asymmetrical Normative Entrapment in EU-ACP EPA Negotiations. Aalborg: SPIRIT.

Nichol, J. (2009): Russia-Georgia Conflict in August 2008: Context and Implications for U.S. Interests. Congressional Research Service, 30 March, <accessed online: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL34618.pdf>.

Pavilionis, Ž. (2008): Lithuanian Position Regarding the EU Mandate on Negotiations with Russia: Seeking a New Quality of EU-Russian Relations. Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review, 21, 174–181.

Perlo-Freeman, S., Fleurant, A., Wezeman, P. D. & Wezeman, S. T. (2015): Trends in World Military Expenditure. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April, <accessed online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/193234/SIPRIFS1504.pdf>.

Pollack, M. A. (1996): The New Institutionalism and EC Governance: The Promise and Limits of Institutional Analysis. Governance, 9(4), 429–458.

Przybyło, P. (2019): The Real Financial Cost of Nord Stream 2: Economic Sensitivity Analysis of the Alternatives to the Offshore Pipeline. Casimir Pulaski Foundation, <accessed online: https://pulaski.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Raport_NordStream_TS.pdf>.

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (2008): Has Poland Lifted Its Veto on Russia-EU Talks? Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 25 April, <accessed online: https://www.rferl.org/a/1144100.html>.

Rettman, A. (2006): Polish Veto Derails EU–Russia Summit Agenda. Euobserver, 23 November, <accessed online: https://euobserver.com/foreign/22942>.

Rettman, A. (2018): Merkel: Nord Stream 2 Is 'Political'. Euobserver, 4 November, <accessed online: https://euobserver.com/energy/141570>.

Reuters (2016): Biden: Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Is a 'Bad Deal' for Europe. Reuters, 25 August, <accessed online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-energy-europe-usa/biden-nord-stream-2-pipeline-is-a-bad-deal-for-europe-idUSKCN1101AP>.

Ricks, J. I. & Liu, A. H. (2018): Process-Tracing Research Designs: A Practical Guide. Political Science and Politics, 51(4): 842–846.

Schmidt-Felzmann, A. (2008): All for One? EU Member States and the Union's Common Policy Towards the Russian Federation. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 16(2), 169–187.

Shelton, J. (2019): France Set to Undermine Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Deal. DW News, 2 July, <accessed online: https://www.dw.com/en/france-set-to-undermine-nord-stream-2-pipeline-deal/a-47414743>.

Siddi, M. (2018a): A Contested Hegemon? Germany’s Leadership in EU Relations with Russia. German Politics, 94, 1–18.

Siddi, M. (2018b): The Role of Power in EU–Russia Energy Relations: The Interplay between Markets and Geopolitics. Europe-Asia Studies, 70(10), 1552–1571.

Spiegel International (2006): Poland Veto Escalates Beef with Moscow. Spiegel International, 24 November, <accessed online: https://www.spiegel.de/international/eu-russian-summit-in-helsinki-poland-veto-escalates-beef-with-moscow-a-450496.html>.

Szul, R. (2011): Geopolitics of Natural Gas Supply in Europe - Poland between the EU and Russia. European Spatial Research and Policy, 18(2), 47-67.

Tallberg, J. (2008): Bargaining Power in the European Council. Journal of Common Market Studies, 46(3), 685–708.

Thomas, D. C. (2009): Explaining the Negotiation of EU Foreign Policy: Normative Institutionalism and Alternative Approaches. International Politics, 46(4), 339–357.

Thucydides, Hammond, M., Rhodes, P. J. (2009): The Peloponnesian War. New York: Oxford University Press.

Times of Malta (2008): Lithuania Ready to Confront EU on Russia Talks. Times of Malta, 25 April, <accessed online: https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/lithuania-ready-to-confront-eu-on-russia-talks.205464.amp>.

Vaughan, A. (2019): Nord Stream 2 Russian Gas Pipeline Likely to Go Ahead after EU Deal. The Guardian, 25 February, <accessed online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/feb/25/nord-stream-2-russian-gas-pipeline-likely-to-go-ahead-after-eu-deal>.

Viceré, M. G. A. (2016): The Roles of the President of the European Council and the High Representative in Leading EU Foreign Policy on Kosovo. Journal of European Integration, 38(5), 557–570.

Vitkus, G. (2009): Russian Pipeline Diplomacy: A Lithuanian Response. Acta Slavica Iaponica, 26, 25–46. <accessed online: https://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/publictn/acta/26/02Vitkus.pdf>.

Waltz, K. N. (1979): Theory of International Politics. Philippines: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Warntjen, A. (2010): Between Bargaining and Deliberation: Decision-Making in the Council of the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(5), 665–679.

World Bulletin (2008): Poland to Drop Veto on New EU-Russian Partnership Agreement. World Bulletin, 21 January, <accessed online: https://www.worldbulletin.net/archive/poland-to-drop-veto-on-new-eu-russian-partnership-agreement-h16970.html>.

Worldometers (2019): European Countries by Population. Worldometers, <accessed online: https://www.worldometers.info/population/countries-in-europe-by-population

[1] It is worth mentioning that while the EU admitted that Poland had ignored some of the EU standards for exporting meat, they held that the sanction was not proportionate. This sanction cost Poland one million dollars per day (Rettman 2006) and it expected support from the EU against Russia (Spiegel Online 2006). Despite intensive negotiations, Poland insisted that it would not withdraw its veto and asked for a permanent veto mechanism that could constantly block the negotiations. This was rejected, but the EU president offered a political declaration on EU ‘solidarity’ (Rettman 2006). What Poland looked for was a guarantee that the EU would put pressure on Russia until it lifted its sanctions but the idea was dismissed. However, the Commission president promised the Polish prime minister that the EU would stop negotiations if Russia used ‘dirty tricks’ against Poland and both trade and health commissioners asked Russia to take part in a trilateral talk involving Warsaw. But not much more was done.

[2] In 2006, when Lithuania sold Mažeikiai refinery to a Polish investor instead of a Russian investor, Russia stopped oil export to Lithuania with the excuse of the maintenance operation of the Druzhba pipeline and refused Lithuania’s help to expedite the operation (Pavilionis 2008: 175–176). This caused a great financial loss to the refinery (Vitkus 2009: 32).

[3]After Georgia’s president warned that Abkhazia’s separatists were supported by Russia, the Lithuanian foreign minister announced that the tension was highly related to Lithuania’s security concerns too (Deutsche Welle 2008b).

[4] Alexander Litvinenko was a former officer in Russia’s FSB spy agency who had been poisoned in London in 2006, but Moscow refused to extradite the main suspect to London (Times of Malta 2008).

[5] The exact wording of the compromise was that oversight comes from the ‘territory and territorial sea of the member state where the first interconnection point is located’ ( Deutsche Welle 2019).